In the novel Dr No, as James Bond flies into Kingston airport at the start of his investigation of Dr No's nefarious activities (Dr No, chapter 4), he runs into a photographer from the Daily Gleaner, who is eager to take Bond's picture. Bond is understandably keen to remain in the shadows and is worried about details of his visit reaching the paper. When Ian Fleming wrote this episode, which also appeared in the screen adaptation, he was writing from personal experience. Like Bond, he invariably gained the attention of the Press on his arrival in Jamaica, but, at least in the early days, he had his own reasons for wanting to keep his visits low key.

When celebrities came to Jamaica, the Daily Gleaner made sure that its readers knew about it. The paper even had a dedicated column, “Airport News”, to report the arrival and departure of notable visitors. Ian Fleming built Goldeneye, his Jamaican home, in 1946, and very soon afterwards the Gleaner, initially because of Fleming's association with the wealthy so-called 'resident-visitor' Ivor Bryce, had recognised Fleming as someone newsworthy. In February 1947, the Gleaner ran a story about wealthy visitors buying property in Montego Bay, and mentioned Fleming's recent purchase.

By 1947, Ian Fleming's relationship with Lady Ann Rothermere, the wife of newspaper proprietor Lord Rothermere, was some six years old. Ian and Ann were determined to keep their affair discreet, and on her first visit to Goldeneye in 1948, Ann had brought Loelia, Duchess of Westminster as a chaperone to help deflect suspicions and gossip.

Ann and Ian's flight into Kingston (Palidadoes) Airport on 12th January, however, had not passed unnoticed, and the following day, their arrival was reported in the Daily Gleaner. Fortunately for Ian and Ann, the piece, accompanied by a photograph of the couple, revealed nothing of their relationship, and appeared to suggest that Ian and Ann had to some extent made separate holiday plans. Readers learnt that Ann was to be in Jamaica for three weeks and was to stay with Ivor Bryce, as well as Ian Fleming, while Ian was planning to remain in the country for six weeks at Goldeneye.

When Fleming described James Bond's arrival into Jamaica in Dr No (1958), he was in essence recalling his own experience. The Gleaner's reporter who greets Bond at the airport asks Bond the same questions that the reporter must have asked Fleming: how long will you be in Jamaica ('in transit', Bond answers), and where will you staying ('Myrtle Bank')? There was also a flash of the camera and the prospect of Bond's picture appearing in print.

Ian Fleming drew from a wide range of sources and experiences when he wrote the James Bond books. Some of these experiences, such as his wartime role and post-war journalism, form an important part of Bond's character and adventures. But there are other, seemingly less significant events, including arriving in Jamaica, which also contribute and add fine detail to the stories.

Pages

▼

Sunday, 25 November 2012

Sunday, 18 November 2012

History lessons in the Bond films

I used to teach archaeology at a further education college, and when I got to the session on ancient Roman temples, I put From Russia With Love in the dvd player and showed my students the scenes at the Hagia Sophia, a late Roman church, and later a mosque, in Istanbul (and seen also fleetingly in Skyfall). Sometimes I forgot to switch the film off, and we ended up watching rather more of the film that I intended. My students may not have learned much about Roman religious buildings, but at least they received a thorough grounding in the history of James Bond.

Something that adds colour and depth to a Bond film is the attention paid to the local cultural background. This has often included aspects of local heritage, and over course of the series, film-viewers have, for example, visited Karnak and the pyramids at Giza in Egypt, accompanied a tour of a museum of antique glass in Venice (the museum was a film set, but Venice nonetheless has a long tradition of glass-making that dates back to the 13th century), and, most recently in Skyfall, had a small introduction to 16th-century priest holes in Scotland.

As an archaeologist, I have always been particularly interested in the heritage shown in From Russia With Love. The scenes at the Hagia Sophia are fascinating. As Tatiana Romanova enters the site, we see a guide take a party of tourists across the floor of the building. As far as tours go, the guide's technique is pretty poor. There is no sense of chronological sequence, and he talks of noteworthy objects in a seemingly random way.

That is not to say that the information given by the guide is especially inaccurate. The guide points out two alabaster urns dating to the Hellenistic period (4th to 1st century BC), which were brought from the ancient city of Pergamon to Istanbul by Sultan Murad IV. This was indeed the case, although not, as the guide tells us, in 1648, but sometime between 1574 and 1595. The urns continue to stand on opposite sides of the nave.

The wishing column that the guide also mentions stands at the north-west end of the building. Legend has it that the late Roman emperor Justinian, while suffering with a headache, rested his head on the column and the pain ceased. Visitors have been touching the column ever since and it has taken its place among the notable features of the building.

Another feature described by the guide is the ablution fountain. This is actually located outside the main building and was built by Sultan Mahmud I in 1740.

We don't know James Bond's opinion of Hagia Sophia, but he seems unimpressed by Istanbul's subterranean late Roman cistern. Bond meets Kerim Bey's brief description of the structure as they descend some steps and climb into a boat with a bored, 'really?' Kerim Bey tells Bond that the reservoir was built by the emperor Constantine 1600 years ago. This isn't strictly true. Known as the Basilica Cistern, the structure was built during the reign of Justinian 1400 years ago on the site of an earlier Roman basilica or market hall.

The Bond films remain a source of interesting cultural information that adds depth and credibility to the story. While accuracy has sometimes been sacrificed for cinematic purposes, the inclusion of local heritage is testament to the film-makers attention to detail and respect for the regions in which they are filming.

Photo credits:

Hagia Sophia (Urn, Wishing Column and ablution fountain): JoJan (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic )

Basilica Cistern: Public domain image by Gryffindor

Something that adds colour and depth to a Bond film is the attention paid to the local cultural background. This has often included aspects of local heritage, and over course of the series, film-viewers have, for example, visited Karnak and the pyramids at Giza in Egypt, accompanied a tour of a museum of antique glass in Venice (the museum was a film set, but Venice nonetheless has a long tradition of glass-making that dates back to the 13th century), and, most recently in Skyfall, had a small introduction to 16th-century priest holes in Scotland.

As an archaeologist, I have always been particularly interested in the heritage shown in From Russia With Love. The scenes at the Hagia Sophia are fascinating. As Tatiana Romanova enters the site, we see a guide take a party of tourists across the floor of the building. As far as tours go, the guide's technique is pretty poor. There is no sense of chronological sequence, and he talks of noteworthy objects in a seemingly random way.

That is not to say that the information given by the guide is especially inaccurate. The guide points out two alabaster urns dating to the Hellenistic period (4th to 1st century BC), which were brought from the ancient city of Pergamon to Istanbul by Sultan Murad IV. This was indeed the case, although not, as the guide tells us, in 1648, but sometime between 1574 and 1595. The urns continue to stand on opposite sides of the nave.

The wishing column that the guide also mentions stands at the north-west end of the building. Legend has it that the late Roman emperor Justinian, while suffering with a headache, rested his head on the column and the pain ceased. Visitors have been touching the column ever since and it has taken its place among the notable features of the building.

Another feature described by the guide is the ablution fountain. This is actually located outside the main building and was built by Sultan Mahmud I in 1740.

We don't know James Bond's opinion of Hagia Sophia, but he seems unimpressed by Istanbul's subterranean late Roman cistern. Bond meets Kerim Bey's brief description of the structure as they descend some steps and climb into a boat with a bored, 'really?' Kerim Bey tells Bond that the reservoir was built by the emperor Constantine 1600 years ago. This isn't strictly true. Known as the Basilica Cistern, the structure was built during the reign of Justinian 1400 years ago on the site of an earlier Roman basilica or market hall.

The Bond films remain a source of interesting cultural information that adds depth and credibility to the story. While accuracy has sometimes been sacrificed for cinematic purposes, the inclusion of local heritage is testament to the film-makers attention to detail and respect for the regions in which they are filming.

Photo credits:

Hagia Sophia (Urn, Wishing Column and ablution fountain): JoJan (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic )

Basilica Cistern: Public domain image by Gryffindor

Friday, 9 November 2012

Bond girls, villains and catchphrases: some analysis

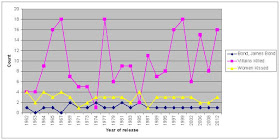

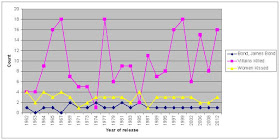

Among the many articles about James Bond published in recent weeks ahead of the release of Skyfall was an interesting piece for the BBC news website, titled 'James Bond: cars, catchphrases and kisses'. The item, researched and compiled by Helene Sears, Tom Housden, Mark Savage, and Steven Atherton, attempted to present “definitive data on women kissed, villains dispatched and catchphrases [specifically 'Bond, James Bond'] uttered.” While there are arguably more interesting statistics, for example the number of martinis consumed, one-liners delivered, or gadgets used (though see my own data on Bond's drinks and gadgets), the data were presented in the form of counts, and, as I can't resist playing with data, I thought I'd carry out some analysis on the numbers to identify any further insights on the evolution of the film series and the differences in the way Bond has been portrayed.

According to the BBC article, the total number of villains killed is 218. Sixty-four women have been kissed, while 'Bond, James Bond' has been said 25 times. Over the 23-film series, an average of 9.5 villains have been killed per film, while each film has seen an average of 2.8 women kissed. 'Bond, James Bond' has been uttered an average of 1.1 times per film.

Looking at the individual Bond actors, Sean Connery's Bond has been responsible, on average, for the deaths of 9.3 villains. This compares with 7 villains for George Lazenby, 7.1 for Roger Moore, nine for Timothy Dalton, 12 for Pierce Brosnan, and 13 villains for Daniel Craig. These values suggest that there has been an increase over the course of the series in the number of villains killed per film. Notably, the standard deviation for Sean Connery (6.3 villains) is larger than that, say, for Pierce Brosnan (5.9), pointing to a more variable record for Connery's Bond. In other words, some of Connery's films have relatively few deaths (as few as four), while others are far more lethal, with as many as 18 deaths. The body count in Brosnan's films, by comparison, is generally higher (ranging from 8 to 18).

Turning to the number of women kissed, Sean Connery's Bond kissed on average three women per film. George Lazenby also kissed three women in his single film, and Pierce Brosnan's average is three as well. Roger Moore's Bond has a slightly lower average of 2.9 women kissed, and Daniel Craig's average is lower still – 2.3 women kissed per film. Timothy Dalton has the lowest average, just two women kissed per film, although Dalton's dataset of just two films is really too small for statistical purposes; after all, Dalton's Bond kissed three women in Licence to Kill, which is above the series average. As with the villains killed category, the standard deviation for Sean Connery is higher than that for Roger Moore (1.3 women kissed, compared with 0.7), suggesting that Connery's Bond is again the most variable (the range of Connery's Bond is between 1 and 4 women kissed).

Of the catchphrase, 'Bond, James Bond', there is very little variation across the film series; the phrase has more or less been uttered once in every film. The phrase, however, has not been used in every Connery film, and only George Lazenby and Roger Moore have used the phrase twice in a single film.

Some of the trends outlined above also emerge when we examine the data from a chronological perspective. From the chart, the general increase in the number of villains killed over time is clear, although there has been enormous fluctuation throughout the series. Connery's films quickly ramped up the body count as each film attempted to better the last, and some of the most spectacular films, including You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me, and The World is not Enough, have had high values to match – 18 villain-deaths each. The Roger Moore era (1973-85), in contrast, is generally characterised by the fewest villain-deaths, a product, perhaps, of Moore's take on the role of Bond; Roger Moore has often said that his Bond didn't like to kill and was more likely to use brains rather than violence to get him out of trouble.

As for utterances of 'Bond, James Bond', the trend is flatter still, but where there is fluctuation, it occurs in the Sean Connery and Roger Moore eras, and it is only from the Timothy Dalton era onwards that the numbers largely settle down. A possible reason for this may be that the 'Bond formula' became especially fixed after the Moore era, particularly following the introduction of Pierce Brosnan's Bond in 1995.

In the early films, as the series was establishing itself, there was more room for variation and experimentation, and essential series traits or memes had yet to become well established in popular culture. The Moore era saw a certain redefining of some of these traits initially to establish the actor in the part of Bond and separate his portrayal from Connery's (Moore's Bond, for instance, never ordered a drink 'shaken, not stirred'). The Moore style was then repeated until the introduction of Timothy Dalton in The Living Daylights. As the 1990s ushered in the Brosnan era, there was a certain expectation of what memes should be included and how they could be expressed. This appears to be the case with the phrase, 'Bond, James Bond'. The phrase is now hugely anticipated, causing a frisson when it occurs (just think of the cheer that greeted Bond's utterance of the phrase at the end of Casino Royale). The weight placed on the phrase naturally leads to its use being restricted; if repeated often in the same film, then the phrase is devalued.

The Daniel Craig era has seen a 'reboot' and a desire to re-introduce or even discard elements of Bond lore. The amount of discussion (and ire) that has met these changes – notably the repositioning of the gun barrel – is a measure of how successfully series traits or memes have become embedded in the cultural environment, and how rigidly the Bond formula has been applied in recent decades.

To see the data on which this analysis is based, please click here.

According to the BBC article, the total number of villains killed is 218. Sixty-four women have been kissed, while 'Bond, James Bond' has been said 25 times. Over the 23-film series, an average of 9.5 villains have been killed per film, while each film has seen an average of 2.8 women kissed. 'Bond, James Bond' has been uttered an average of 1.1 times per film.

Looking at the individual Bond actors, Sean Connery's Bond has been responsible, on average, for the deaths of 9.3 villains. This compares with 7 villains for George Lazenby, 7.1 for Roger Moore, nine for Timothy Dalton, 12 for Pierce Brosnan, and 13 villains for Daniel Craig. These values suggest that there has been an increase over the course of the series in the number of villains killed per film. Notably, the standard deviation for Sean Connery (6.3 villains) is larger than that, say, for Pierce Brosnan (5.9), pointing to a more variable record for Connery's Bond. In other words, some of Connery's films have relatively few deaths (as few as four), while others are far more lethal, with as many as 18 deaths. The body count in Brosnan's films, by comparison, is generally higher (ranging from 8 to 18).

Turning to the number of women kissed, Sean Connery's Bond kissed on average three women per film. George Lazenby also kissed three women in his single film, and Pierce Brosnan's average is three as well. Roger Moore's Bond has a slightly lower average of 2.9 women kissed, and Daniel Craig's average is lower still – 2.3 women kissed per film. Timothy Dalton has the lowest average, just two women kissed per film, although Dalton's dataset of just two films is really too small for statistical purposes; after all, Dalton's Bond kissed three women in Licence to Kill, which is above the series average. As with the villains killed category, the standard deviation for Sean Connery is higher than that for Roger Moore (1.3 women kissed, compared with 0.7), suggesting that Connery's Bond is again the most variable (the range of Connery's Bond is between 1 and 4 women kissed).

Of the catchphrase, 'Bond, James Bond', there is very little variation across the film series; the phrase has more or less been uttered once in every film. The phrase, however, has not been used in every Connery film, and only George Lazenby and Roger Moore have used the phrase twice in a single film.

Some of the trends outlined above also emerge when we examine the data from a chronological perspective. From the chart, the general increase in the number of villains killed over time is clear, although there has been enormous fluctuation throughout the series. Connery's films quickly ramped up the body count as each film attempted to better the last, and some of the most spectacular films, including You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me, and The World is not Enough, have had high values to match – 18 villain-deaths each. The Roger Moore era (1973-85), in contrast, is generally characterised by the fewest villain-deaths, a product, perhaps, of Moore's take on the role of Bond; Roger Moore has often said that his Bond didn't like to kill and was more likely to use brains rather than violence to get him out of trouble.

As for utterances of 'Bond, James Bond', the trend is flatter still, but where there is fluctuation, it occurs in the Sean Connery and Roger Moore eras, and it is only from the Timothy Dalton era onwards that the numbers largely settle down. A possible reason for this may be that the 'Bond formula' became especially fixed after the Moore era, particularly following the introduction of Pierce Brosnan's Bond in 1995.

In the early films, as the series was establishing itself, there was more room for variation and experimentation, and essential series traits or memes had yet to become well established in popular culture. The Moore era saw a certain redefining of some of these traits initially to establish the actor in the part of Bond and separate his portrayal from Connery's (Moore's Bond, for instance, never ordered a drink 'shaken, not stirred'). The Moore style was then repeated until the introduction of Timothy Dalton in The Living Daylights. As the 1990s ushered in the Brosnan era, there was a certain expectation of what memes should be included and how they could be expressed. This appears to be the case with the phrase, 'Bond, James Bond'. The phrase is now hugely anticipated, causing a frisson when it occurs (just think of the cheer that greeted Bond's utterance of the phrase at the end of Casino Royale). The weight placed on the phrase naturally leads to its use being restricted; if repeated often in the same film, then the phrase is devalued.

The Daniel Craig era has seen a 'reboot' and a desire to re-introduce or even discard elements of Bond lore. The amount of discussion (and ire) that has met these changes – notably the repositioning of the gun barrel – is a measure of how successfully series traits or memes have become embedded in the cultural environment, and how rigidly the Bond formula has been applied in recent decades.

To see the data on which this analysis is based, please click here.

Sunday, 4 November 2012

Download the complete guide to James Bond's drinks free

To celebrate the US release of Skyfall on 8th November, David Leigh's The Complete Guide to the Drinks of James Bond is available free for Kindle from Amazon. This is the second edition of the book by David, who also runs the James Bond Dossier website, and includes the drinks of the current Bond film.

The book, which brings together the drinks of both the film series and Fleming's novels, is excellent and a must for Bond afficiandos. And, given the furore surrounding the use of Heineken in Skyfall, it is a reminder that James Bond is an occasional beer drinker.

As David says, 'many people were unhappy at the announcement earlier this year that James Bond would be seen drinking Heineken beer in Skyfall. However, this really isn't a big deal for a number of reasons: first, 007 drank beer in several of the books; second, don't think that he only drinks beer in Skyfall; and third, while most people associate vodka martinis and champagne with 007, he actually drinks more whisky in the novels anyway'.

Download the book for free until 7th November 7 2012 (Pacific Standard Time) from your local Amazon store.

The book, which brings together the drinks of both the film series and Fleming's novels, is excellent and a must for Bond afficiandos. And, given the furore surrounding the use of Heineken in Skyfall, it is a reminder that James Bond is an occasional beer drinker.

As David says, 'many people were unhappy at the announcement earlier this year that James Bond would be seen drinking Heineken beer in Skyfall. However, this really isn't a big deal for a number of reasons: first, 007 drank beer in several of the books; second, don't think that he only drinks beer in Skyfall; and third, while most people associate vodka martinis and champagne with 007, he actually drinks more whisky in the novels anyway'.

Download the book for free until 7th November 7 2012 (Pacific Standard Time) from your local Amazon store.

Saturday, 3 November 2012

James Bond's papal blessing

It's official. The pope is a James Bond fan. In a surprise move, the Vatican's daily newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, gave its blessing to James Bond recently with the publication of a glowing review of Skyfall and a series of features on the Bond phenomenon. The paper praised Judy Dench as the 'perfect M', Javier Bardem's Silva as 'terrific', and Daniel Craig's Bond as 'more human'. Skyfall is, in the paper's view, 'one of the best in the longest cinematic story of all time'.

The review represents a significant shift for the Vatican. In 1965, L'Osservatore Romano denounced the James Bond films and what the paper felt they represented. Dr No was 'a mixture of violence, vulgarity, sadism and sex', and the paper hoped that the film had not met with the success that it did. Of the subsequent films, the newspaper found their consistency 'deplorable but explicable'.

Similar views on James Bond were held by other well-known Catholics at the time and could be said to represent something of an official line on the Fleming/Bond phenomenon. Paul Johnson, who wrote an infamous 1958 review of the novel, Dr No, for the New Statesman, was a devout Catholic. His view that Fleming 'satisfies the very worst instincts of his readers' and that the book delivers a 'brew of sex and sadism' would no doubt have found wide agreement within the Vatican.

And it was his Catholic faith that prevented Patrick McGoohan pursuing the role of James Bond in 1962. In interviews McGoohan said that he abhorred violence and cheap sex and that society needed moral heroes. In his TV series, Danger Man (broadcast in the US as Secret Agent), the hero John Drake, played by McGoohan, was 'a man of high ideals'. McGoohan said that the series contained 'action, but no brutal violence', and that 'it would have been wrong [for Drake] to get seriously involved with women'.

But religious denunciation of Bond has not been confined to the Catholic church. In 1961, the Rev. Leslie Paxton of the Great George Street Congregational Church in Liverpool preached a sermon against James Bond. Ian Fleming responded with a letter to the reverend, requesting a copy of the sermon in order to understand the nature of the criticisms (but there was apparently no 'death-bed conversion' in Fleming's final novels). And in 1980/1, during location filming of For Your Eyes Only at Meteora, Greece, monks from the Eastern Orthodox Church protested against the use of their monastery in the film, and attempted to spoil the filming by hanging washing out of the windows.

It has taken 50 years for the Vatican to succumb to the charms of James Bond. During that time, the world has seen huge social change. The Vatican is clearly part of society and is not immune to the ever evolving landscape of what is morally acceptable. How else can we explain the fact that aspects of James Bond that caused such consternation for the church in the 1960s are points of celebration in 2012?

References:

Barnes, A and Hearn, M, 1997 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Batsford

Haining, P, 1987 James Bond, a celebration, Planet

Pearson, J, 1966 The life of Ian Fleming, Cape

The review represents a significant shift for the Vatican. In 1965, L'Osservatore Romano denounced the James Bond films and what the paper felt they represented. Dr No was 'a mixture of violence, vulgarity, sadism and sex', and the paper hoped that the film had not met with the success that it did. Of the subsequent films, the newspaper found their consistency 'deplorable but explicable'.

Similar views on James Bond were held by other well-known Catholics at the time and could be said to represent something of an official line on the Fleming/Bond phenomenon. Paul Johnson, who wrote an infamous 1958 review of the novel, Dr No, for the New Statesman, was a devout Catholic. His view that Fleming 'satisfies the very worst instincts of his readers' and that the book delivers a 'brew of sex and sadism' would no doubt have found wide agreement within the Vatican.

And it was his Catholic faith that prevented Patrick McGoohan pursuing the role of James Bond in 1962. In interviews McGoohan said that he abhorred violence and cheap sex and that society needed moral heroes. In his TV series, Danger Man (broadcast in the US as Secret Agent), the hero John Drake, played by McGoohan, was 'a man of high ideals'. McGoohan said that the series contained 'action, but no brutal violence', and that 'it would have been wrong [for Drake] to get seriously involved with women'.

But religious denunciation of Bond has not been confined to the Catholic church. In 1961, the Rev. Leslie Paxton of the Great George Street Congregational Church in Liverpool preached a sermon against James Bond. Ian Fleming responded with a letter to the reverend, requesting a copy of the sermon in order to understand the nature of the criticisms (but there was apparently no 'death-bed conversion' in Fleming's final novels). And in 1980/1, during location filming of For Your Eyes Only at Meteora, Greece, monks from the Eastern Orthodox Church protested against the use of their monastery in the film, and attempted to spoil the filming by hanging washing out of the windows.

It has taken 50 years for the Vatican to succumb to the charms of James Bond. During that time, the world has seen huge social change. The Vatican is clearly part of society and is not immune to the ever evolving landscape of what is morally acceptable. How else can we explain the fact that aspects of James Bond that caused such consternation for the church in the 1960s are points of celebration in 2012?

References:

Barnes, A and Hearn, M, 1997 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Batsford

Haining, P, 1987 James Bond, a celebration, Planet

Pearson, J, 1966 The life of Ian Fleming, Cape