|

| Jack the Bulldog by Royal Doulton. As seen in Spectre |

When we last saw him, Jack, the ceramic union flag-clad bulldog manufactured by Royal Doulton that sat on M's desk, had been bequeathed to James Bond following the death of M at Bond's family home, Skyfall. It is fair to say that Bond was ambivalent about Jack, but Jack must have worked his charm, because he is back in the upcoming Bond film, Spectre.

Royal Doulton began making models of bulldogs during the Second World War. The breed symbolised the determination of the British character, and ceramic models during this time wore flags and uniforms to honour the bravery of military personnel.

The bulldog is, of course, most closely associated with Britain's wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, who came to epitomise the 'bulldog spirit'. To Ian Fleming, Churchill was a hero. Fleming greatly admired him as a wartime leader, but his admiration went back to his childhood, when, during the First World War, Churchill wrote an appreciation, published in The Times, of Fleming's father, who had been killed in action.

Ian Fleming treasured Churchill's words throughout his life, and even gave Churchill a part of sorts in one of his Bond books: in Moonraker (1955) M speaks to the prime minister on the phone, who, given the year in which the adventure is set, must be identified as Churchill. The bulldog-like appearance of Churchill is also referenced. In From Russia, with Love (1957), Fleming mentions Cecil Beaton's portrait of Churchill, whose expression Fleming likens to that of a “contemptuous bulldog”. Considering the connections between Fleming and Churchill, it seems appropriate that Jack the Bulldog should continue his association with the world of James Bond.

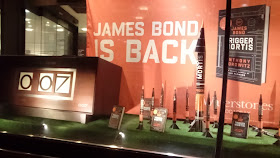

To coincide with the release of Spectre, the new model of Jack the Bulldog, numbered DD 007 M, will be available to order from Royal Doulton in the autumn. Anyone wishing to purchase the model can register with Royal Doulton to receive email alerts when the model is in stock. Click here to find out more. Meanwhile, we wait with interest to see what role Jack will have in Bond's latest adventure.