If you're after a last-minute Christmas gift idea, then your thoughts may have turned to the film of Moonraker. Among the gadgets Q supplies James Bond is a dart gun worn around the wrist. Equipped with ten darts – five amour-piercing, five cyanide-tipped – the device comes in handy when Bond needs to cut the power of a rotating centrifuge trainer and help Drax take a giant step back for mankind. 'Very novel, Q', Bond says. 'Must get them in the stores for Christmas'.

Did Q succeed in getting them in the stores for Christmas? Sadly, no. The Imperial Toys Corporation produced a James Bond dart gun in 1984 (click here for details), but the darts are fired from a standard pistol-type gun, rather than one worn round the wrist. And in any case, the toy, long out of production, is hard to come by.

Replicas of the film's dart gun are built from time to time and become available to buy at specialist stores or auction sites, but a trawl of such places suggests that if you're looking for a replica of the prop, then you're out of luck. Replica dart guns were being sold on eBay for £140 in 2015, but these no longer appear to be available. Vectis Auctions, which specialises in collectible toys, were selling a reproduction of the prop in 2013, but no other examples have been offered since.

I admit I haven't looked at the websites of arms manufacturers, but it's possible that a wrist-mounted dart gun is in development and on the way to becoming science fact.

So, it seems that Q didn't follow Bond's advice. Oh well, there's always next year. In the meantime, have a wonderful Bondian Christmas.

Friday, 23 December 2016

Sunday, 18 December 2016

Organisation heads talk about the pros and cons of association with James Bond

|

| A view of Vauxhall Cross, SIS headquarters |

These relationships with James Bond were raised recently by the head of MI6 (or more properly SIS) and Aston Martin's director of global marketing in statements that were in some ways rather similar. While both acknowledged the benefits their association with James Bond has brought, they also alluded to negative aspects.

In a speech to journalists at Vauxhall Cross earlier this month, the chief of SIS (known as 'C') Alex Younger described how James Bond helped create a powerful brand for SIS that gave the organisation, or at least its name, worldwide recognition. Younger also admitted that SIS requires a deep grasp of gadgets and employs a real-life Q.

But, he continued, James Bond also creates a false picture of the type of people who work for the organisation. There is no single characteristic that defines an SIS officer, whether that be an Oxbridge graduate or an expert in hand-to-hand combat, and James Bond types who are reckless, immoral, or prone to law-breaking need not apply.

Dan Balmer, director of global marketing at Aston Martin, also considered both the positive and negative aspects of an association with James Bond. He told Marketing Week last month that while the company remains open to the opportunities that an association with Bond brings, it relied too much on James Bond in the past. Its marketing, for instance, has tended to focus around the release of new Bond films, the result being that between films people stop talking about the cars and sales suffer.

Balmer spoke about how Aston Martin was planning to move beyond its perceived British and male core market (his comments about Bond hint at the fact that Bond naturally helps reinforce this perception), announcing that its marketing will now be designed to appeal to international audiences and female drivers.

In making their statements, both Alex Younger and Dan Balmer acknowledge the role, whether welcome or not, that James Bond plays in promoting their organisations and maintaining brand awareness. In memetic terms, the Bond films, to which Younger and Balmer alluded, are a highly successful vehicle for spreading ideas or memes about Aston Martin and SIS (even if inaccurate). However, the association between the organisations and Bond is so strong that the films aren't necessary to spread and reinforce those memes. The press and other media also do the job, but the association is so firmly fixed in people's minds, who wittingly or unwittingly pass it on to others, that it is practically self-replicating.

This means that, unfortunately for Alex Younger and Dan Balmer, it'll take a very long time – and the disappearance of Bond from the cultural environment – to change popular perceptions. Aston Martin and SIS will remain synonymous with Bond for a while longer yet.

Sunday, 11 December 2016

Did Phyllis Bottome invent James Bond? The case against

|

| The Lifeline, first edition |

The case that Ian Fleming had substantially based James Bond on the main character and events of Bottome's novel was championed by espionage writer Nigel West. He has form in the matter, having made the case in his 2009 book, Historical Dictionary of Ian Fleming's World of Espionage. West was supported by critic and publisher Simon Winder, who's own book on James Bond, The Man who Saved Britain (2006), far from being a celebration of Fleming's creation, was an exercise in subtle denigration and damning with faint praise.

Casting a more cautious eye on the matter were Pam Hirsch, who wrote a biography of Phyllis Bottome called The Constant Liberal, and John Pearson, the biographer of both Ian Fleming and James Bond.

So what were the principal arguments? The case for the prosecution, as it were, focused on two key points. The first was that the protagonist of The Lifeline, Mark Chalmers, is near-identical to James Bond. Describe Chalmers' appearance (slim, six-feet tall), attitudes (particularly towards women), philosophy, and pastimes (skiing, climbing) without mentioning his name, and anyone listening would think you were describing James Bond.

The second point concerned the events at the end of Bottome's novel. Chalmers, who has been on a secret mission in Austria gathering Nazi secrets for British intelligence on the eve of the Second World War, is captured by the Gestapo, given a severe beating, saved in the nick of time, recuperates in a hospital (actually a mental asylum where Chalmers has been resident as part of his cover), falls in love with a fellow agent (Ida Eichhorn) who has been caring for him and whom he initially disliked, and has a bedside discussion about his purpose and the nature of good and evil with a local contact (Father Martin).

Compare that to the end of Casino Royale, in which Bond is captured by a SMERSH agent, given a severe beating, saved in the nick of time, recuperates in a hospital, falls in love with a fellow agent (Vesper Lynd) who has been caring for him and whom he initially disliked, and has a bedside discussion about his purpose and the nature of good and evil with a local contact (René Mathis).

Of the two arguments, the second is strongest, yet even that only suggests that Fleming was inspired by one specific element of Bottome's book (apparently Bottome sent Fleming all her books, and it is highly likely that he had read The Lifeline before writing Casino Royale). Claiming that Bottome had invented James Bond and that, as was hinted at in the programme, a case of plagiarism could be made against Fleming, is rather more of a leap, and to me is without foundation.

Other points raised by Nigel West are minor and easily dismissed. The spy chief in The Lifeline is called B; Ian Fleming called his M. And Somerset Maugham's spy chief is R and the real one is C. Isn't it more plausible that the naming of M simply follows a convention well established in spy fiction (and reality), rather than the style of a single book? West also suggests that, like Mark Chalmers, Bond can climb like a mountain goat. In the films maybe, but evidence for this in the books, certainly Casino Royale, is lacking.

One obvious difficulty, apart from the fact that Ian Fleming first had the idea for 'the spy story to end all spy stories' during the war and before The Lifeline was published, is that The Lifeline and Casino Royale simply do not compare stylistically. Having read The Lifeline, I can confirm that it reads more like a John Buchan novel than a Fleming novel. It contains long philosophical passages and monologues, and has none of the pace and spare prose of Casino Royale. If Ian Fleming used The Lifeline as a model, then he failed miserably to follow it.

Another problem is that the events depicted in Casino Royale, except those at the end, do not mirror the events of The Lifeline whatsoever. In fact, James Bond would not feature in an Alpine-set adventure until On Her Majesty's Secret Service, published 10 years after Casino Royale. And Fleming's only story set in Austria, 'Octopussy', has Bond in a peripheral role – in Jamaica.

True, the character of Mark Chalmers is similar to Bond, but then again, so too is Ian Fleming; there is no dispute that Fleming gave Bond many of his own traits. It is worth pointing out as well (not mentioned in the documentary) that Ian Fleming acknowledged that the events of Casino Royale were based on his own experiences in the casino of Estoril in Portugal. Nigel West makes the supplementary case that Mark Chalmers was based on Ian Fleming, but this has the whiff of a circular argument. James Bond was inspired by Mark Chalmers who was inspired by Ian Fleming who provided the inspiration for James Bond. Why have a middle man at all? It seems to me that there is little need to invoke Mark Chalmers as the catalyst for James Bond when Ian Fleming's own life accounts for many of the details.

Something else that the programme didn't mention was that Ian Fleming was a literary magpie. He read widely, was in awe of certain writers (among them Raymond Chandler and Somerset Maugham), wrote fulsome reviews and bought copies of his favourite books for all his friends. Inevitably, aspects of the books he enjoyed crept into his own work. Indeed, this blog is about the things that inspired Fleming, and identifies the ideas or memes that the Bond novels share with the works of one novelist or another. Most recently, for example, I pointed out similarities between John Buchan's novel, The Three Hostages, and Moonraker, and I have made the case that the Bond novels are a British form of American hard-boiled thriller. This doesn't mean, however, that John Buchan or Raymond Chandler invented James Bond.

James Bond could not have been created unless The Lifeline and other books like it had not existed, just as the work of John le Carré and Len Deighton – the antitheses of Bond – could not have existed without Bond. Culture is created by taking or passing on, building on, and transforming ideas that already exist in the cultural environment. It lives or dies by being replicated (in the case of Bond books by being read and reprinted), exploiting a cultural niche (no one wrote quite the sort of books that Fleming wrote and the public was ready for it), and adapting to changing conditions (being made into Bond films).

So, did Phyllis Bottome invent James Bond? Not in my view, although I accept that Fleming recreated the ending of The Lifeline in Casino Royale. On balance, I'm with Pam Hirsch when she says that Bottome invented Ian Fleming as a writer. Still, I enjoyed the programme, and the fact that such a debate is the subject of a BBC documentary is testament to the continued success and cultural relevance of Ian Fleming's creation.

Sunday, 4 December 2016

On location: James Bond in Paris

Working backwards through the events of the film, the first stop on my Bond itinerary was the Pont Alexandre III that spans the River Seine. James Bond jumps from this bridge on to a boat in pursuit of May Day, who has herself just landed on the vessel after parachuting from the Eiffel Tower. A boat very much like the one Bond encounters was passing underneath the bridge as I looked over the side, and though I wasn't tempted to emulate Bond, I did consider the practicalities of Bond's jump. Not as easy as it looks, I decided.

|

| The Pont Alexandre III in A View To A Kill (top) and now |

|

| Bond approaching a barrier on Quai Branly (top). The site today (bottom) |

|

| The steps at Pont d'Iena in A View To A Kill (top) and today |

|

| View of Quai Branly from the Eiffel Tower (some of which is replicated in the film's Paris poster) |

|

| Terminus Nord, Bond's favourite Parisian hotel |

|

| Fouquet's, Paris |

For the James Bond fan on the look-out for Bond-related locations, Paris has a lot to offer. Not only can you visit some of the places seen on the screen and mentioned in the pages of Bond's adventures, but you can also experience something of the James Bond lifestyle by staying in the hotel Bond stays in or eating or drinking in Bond's favourite restaurants. Just don't go borrowing any taxis.

Monday, 28 November 2016

James Bond referenced in latest Paco Rabanne advert

The latest advert for Paco Rabanne's One Million Privé fragrance has a distinctly Bondian look.

In one TV spot, we see a handsome and cool hero putting on a dinner suit. He clicks his fingers, and the scene switches to a dark space, criss-crossed with laser beams reminiscent of a well-known scene from Mission:Impossible. Our hero energetically negotiates his way around the beams – he is evidently an expert gymnast – before reaching the door to what appears to be a gold vault (shades of Goldfinger?).

The action cuts to another dark empty space, lit only by a spotlight. The man clicks his fingers again, and we see him on top of a skyscraper resembling the Empire State Building like a well-groomed King Kong. The spotlight is moving around looking for him. There is a close up of the man. Keeping with the King Kong allusion, a woman stands on his open hand. The man turns to the camera and clicks his fingers again.

Instantly, the man's appearance changes. He now wears a white dinner jacket and adopts a very familiar pose: he stands facing us, the lower part of his left leg behind his right leg. His left arm is held against his body, his left hand tucked under his right elbow. The lower part of his right arm is bent upwards, his hand resting on his chin as if he is in thought.

If you put a gun in his right hand, then he'd be imitating the classic James Bond pose seen on many posters and publicity shots from the Bond films, beginning with From Russia, With Love. The reference is confirmed as the spotlight captures him, and he is enclosed in a white circle that mimics the gunbarrel sequence that traditionally opens a Bond film.

But he hasn't been caught for long, as he makes an appropriately Bondian escape holding on to the landing skid of a helicopter.

Though short, the advert is crammed with film references, among them references to James Bond (potentially five – the pose, the dinner suit, spotlight, the helicopter and the vault).

The use of the spotlight is itself interesting. In the traditional gunbarrel, it is not a spotlight we see moving across the screen at the start of the gunbarrel sequence, but simply a white dot – or possibly the sights of a gun – that is transformed into the end of a gunbarrel. The dot, however, is similar enough to a spotlight for the spotlight to be used as a proxy by photographers, film-makers and others for the gunbarrel. Simply shine a spotlight on someone and the allusion to Bond is made.

I'm reminded of the cover of the Mail on Sunday's Event magazine in August last year, which showed Anthony Horowitz caught by a spotlight. Whetting readers' appetites for a feature about Horowitz's James Bond novel, the image was clearly meant to recall the gunbarrel sequence (although there is something Tintin-esque about it too, which may also have been intended, since Horowitz is a fan of Hergé's creation).

In one TV spot, we see a handsome and cool hero putting on a dinner suit. He clicks his fingers, and the scene switches to a dark space, criss-crossed with laser beams reminiscent of a well-known scene from Mission:Impossible. Our hero energetically negotiates his way around the beams – he is evidently an expert gymnast – before reaching the door to what appears to be a gold vault (shades of Goldfinger?).

The action cuts to another dark empty space, lit only by a spotlight. The man clicks his fingers again, and we see him on top of a skyscraper resembling the Empire State Building like a well-groomed King Kong. The spotlight is moving around looking for him. There is a close up of the man. Keeping with the King Kong allusion, a woman stands on his open hand. The man turns to the camera and clicks his fingers again.

Instantly, the man's appearance changes. He now wears a white dinner jacket and adopts a very familiar pose: he stands facing us, the lower part of his left leg behind his right leg. His left arm is held against his body, his left hand tucked under his right elbow. The lower part of his right arm is bent upwards, his hand resting on his chin as if he is in thought.

If you put a gun in his right hand, then he'd be imitating the classic James Bond pose seen on many posters and publicity shots from the Bond films, beginning with From Russia, With Love. The reference is confirmed as the spotlight captures him, and he is enclosed in a white circle that mimics the gunbarrel sequence that traditionally opens a Bond film.

But he hasn't been caught for long, as he makes an appropriately Bondian escape holding on to the landing skid of a helicopter.

Though short, the advert is crammed with film references, among them references to James Bond (potentially five – the pose, the dinner suit, spotlight, the helicopter and the vault).

The use of the spotlight is itself interesting. In the traditional gunbarrel, it is not a spotlight we see moving across the screen at the start of the gunbarrel sequence, but simply a white dot – or possibly the sights of a gun – that is transformed into the end of a gunbarrel. The dot, however, is similar enough to a spotlight for the spotlight to be used as a proxy by photographers, film-makers and others for the gunbarrel. Simply shine a spotlight on someone and the allusion to Bond is made.

I'm reminded of the cover of the Mail on Sunday's Event magazine in August last year, which showed Anthony Horowitz caught by a spotlight. Whetting readers' appetites for a feature about Horowitz's James Bond novel, the image was clearly meant to recall the gunbarrel sequence (although there is something Tintin-esque about it too, which may also have been intended, since Horowitz is a fan of Hergé's creation).

Thursday, 17 November 2016

Skyfall - Home Alone or John Buchan?

The defence of Skyfall, James Bond's family home in the Scottish Highlands, against an assault by Raoul Silva and his small army in the 2012 film has been dismissed by critics as James-Bond-does-Home-Alone. I think the criticism is unfair. Not only is Home Alone a good film, but the critics are also ignoring a more fitting, literary parallel – one from the pages of John Buchan.

In a recent post, I explored the similarities between the novel of Moonraker and John Buchan's fourth Richard Hannay adventure, The Three Hostages. It seems that Skyfall also has some Buchan blood, in this case from his fifth Hannay novel, The Island of Sheep (1936).

When Valdemar Haraldsen's life is threatened by a gang of villains led by master-criminal d'Ingraville, who are pursuing by any means a claim on a 'great treasure' discovered by Haraldsen's late father, Haraldsen turns to Richard Hannay, Hannay's fellow adventurer Lord Clanroyden (formerly Sandy Arbuthnot) and an old friend of Hannay's, Mr Lombard, for help. All three had sworn an oath to Haraldsen's father to protect his son should ever the need arise.

At first, Haraldsen is persuaded to hole up at Laverlaw, Clanroyden's ancestral home in the Scottish Highlands. As Sandy explains, 'The fight must come, and I want to choose my own ground for it... Haraldsen will be safe at Laverlaw till we see how things move.' Unfortunately for Haraldsen, things move rather too quickly, as d'Ingraville and his men are drawn to the estate and make their presence felt.

Haraldsen must retreat further, this time to his own ancestral home on the Island of Sheep in the Norlands (probably the Faroe Islands). Echoing Clanroyden's views, he shares an old proverb with Hannay that 'strongest is every man in his own house.' Clanroyden agrees, and tells Hannay again that 'we must fight them, and choose our own ground for it, and since they are outside civilisation, we must be outside it too.'

James Bond has the same idea in Skyfall. Laying a trail for Silva to follow, Bond tells M that he's taking her 'back in time. Somewhere we'll have the advantage.' Arriving at the lodge, Bond tells the family gamekeeper, Kincade, that 'some men are coming to kill us. But we're going to kill them first.'

Once at the house, Hannay and the others start making preparations for its defence, rather as Bond, Kincade and M do at Skyfall. They shutter the windows and barricade the doors with furniture, and take positions at various parts of house armed with revolvers, rifles and double-barrelled shotguns.

And just as Skyfall has a secret passage – a priest-hole – that leads Kincade and M, and later Bond, away from the house and towards the chapel, Haraldsen's house boasts a little stone cell once occupied by an Irish hermit that takes people away from the house unnoticed via a set of steps to the entrance of a cave by the sea.

Haraldsen's house has no name – it is simply known as the House – but Buchan gives an interesting name to the island's principal hill: Snowfell. The name is obviously not so very different from Skyfall.

The similarity between the scenes at Skyfall in the film of the same name and the passages set on the Island of Sheep in John Buchan's novel may well be coincidence, but if the events of The Island of Sheep had been described in a Bond novel, then we would have no hesitation in claiming that the scenes in Skyfall were based on them. In any case, the similarity indicates that the Skyfall scenes have a literary antecedent. Just as the Bond novel Moonraker can trace its origins to the adventures of Richard Hannay, it seems that Skyfall has also inherited tropes or memes from Buchan's work.

In a recent post, I explored the similarities between the novel of Moonraker and John Buchan's fourth Richard Hannay adventure, The Three Hostages. It seems that Skyfall also has some Buchan blood, in this case from his fifth Hannay novel, The Island of Sheep (1936).

|

| The Island of Sheep, 2012 Polygon edition |

At first, Haraldsen is persuaded to hole up at Laverlaw, Clanroyden's ancestral home in the Scottish Highlands. As Sandy explains, 'The fight must come, and I want to choose my own ground for it... Haraldsen will be safe at Laverlaw till we see how things move.' Unfortunately for Haraldsen, things move rather too quickly, as d'Ingraville and his men are drawn to the estate and make their presence felt.

Haraldsen must retreat further, this time to his own ancestral home on the Island of Sheep in the Norlands (probably the Faroe Islands). Echoing Clanroyden's views, he shares an old proverb with Hannay that 'strongest is every man in his own house.' Clanroyden agrees, and tells Hannay again that 'we must fight them, and choose our own ground for it, and since they are outside civilisation, we must be outside it too.'

James Bond has the same idea in Skyfall. Laying a trail for Silva to follow, Bond tells M that he's taking her 'back in time. Somewhere we'll have the advantage.' Arriving at the lodge, Bond tells the family gamekeeper, Kincade, that 'some men are coming to kill us. But we're going to kill them first.'

Once at the house, Hannay and the others start making preparations for its defence, rather as Bond, Kincade and M do at Skyfall. They shutter the windows and barricade the doors with furniture, and take positions at various parts of house armed with revolvers, rifles and double-barrelled shotguns.

And just as Skyfall has a secret passage – a priest-hole – that leads Kincade and M, and later Bond, away from the house and towards the chapel, Haraldsen's house boasts a little stone cell once occupied by an Irish hermit that takes people away from the house unnoticed via a set of steps to the entrance of a cave by the sea.

Haraldsen's house has no name – it is simply known as the House – but Buchan gives an interesting name to the island's principal hill: Snowfell. The name is obviously not so very different from Skyfall.

The similarity between the scenes at Skyfall in the film of the same name and the passages set on the Island of Sheep in John Buchan's novel may well be coincidence, but if the events of The Island of Sheep had been described in a Bond novel, then we would have no hesitation in claiming that the scenes in Skyfall were based on them. In any case, the similarity indicates that the Skyfall scenes have a literary antecedent. Just as the Bond novel Moonraker can trace its origins to the adventures of Richard Hannay, it seems that Skyfall has also inherited tropes or memes from Buchan's work.

Friday, 11 November 2016

A look at the Bond parody 'Kiss the Girls and Make Them Spy'

If being honest, even the most ardent of fans would concede that Ian Fleming's novels are very much of their time and contain aspects which sit uncomfortably with modern attitudes. Take the representation of homosexuality. To Fleming's credit, there are a few characters who are gay or are hinted to be gay, but their portrayal is problematic. Pussy Galore and Rosa Klebb are the lesbians of heterosexual male fantasy, and in the case of Scaramanga and Wint and Kidd, the homosexuality is a symptom of an abnormality that in part explains the criminal behaviour.

To be fair, Bond's attitude to homosexuality, as suggested for instance by his discussion with Troop about 'intellectuals' in the the Secret Service, is reasonably progressive for the time (it should be remembered that homosexual acts in private were not decriminalised in the UK until 1967), and this no doubt reflects Fleming's own relatively liberal views. After all, some of Fleming's best friends were gay.

However, it is not the gay characters that have made the Bond novels easy targets for camp parodies (we could blame instead Bond's particular habits, for instance in relation to food, and the homoerotic quality of Bond being hit on the genitals with a carpet beater), of which Cyril Connolly's 'Bond Strikes Camp' and 'The Spy who Minced in from the Cold', by Stanley Reynolds are notable examples. A rather more thoughtful parody, however, is Kiss the Girls and Make Them Spy (Harper Collins, 2001), by Mabel Maney.

The novel, set in 1965, concerns an attempt by a secret organisation, the Sons of Britain Society, to depose the Queen and return the Duke of Windsor to the throne. Enter Her Majesty's Secret Service, whose officers serve to protect the Queen, and another mysterious organisation, the Greater European Organization of Radical Girls Inderdicting Evil (G.E.O.R.G.I.E.), which is populated by lesbians sworn to protect the world from destruction wrought by men. Curiously, though, both the Secret Service and G.E.O.R.G.I.E. appear to be oblivious to the plot to kidnap the Queen until it's in full swing.

Meanwhile, James Bond is on sick leave, having suffered a nervous breakdown. In order to preserve the reputation of the Secret Service and the belief that England's top agent is still on active duty, his sister, Jane, who looks very much like James, is blackmailed by the service to take James' place. Jane's mission is to receive a medal from the Queen without raising suspicion.

James Bond's absence is, I suspect, designed to avoid breaching copyright, and there are other changes in personnel; M become N, Miss Moneypenny becomes Miss Tuppenny (and, incidentally, the head of G.E.O.R.G.I.E), and, borrowing from the films, Q becomes X. The author is familiar with the Bond novels: Jane has an unruly comma of hair, as does James, there is reference to the 'powder vine', and it's revealed that Jane's handler, Agent Pumpernickel, or 001, has a S-shaped scar on his cheek, which was made by an enemy agent to mark him as a spy. The scar not only recalls the scar that Fleming's Bond has on his cheek, but also the knife cut in the form of an inverted M that Bond receives on the back of his hand in Casino Royale.

That said, the author doesn't stick rigidly to the 'facts' of Fleming's novels. The Secret Service in Mabel Maney's novel is usually referred to as Her Majesty's Secret Service, operates in England, and exists solely to protect the Queen, just as the US Secret Service is tasked with protecting the President. And, of course, family details are wrong. Apart from the sister we never knew about, James' mother is called Sylvia, and his father, James Bond Sr, was a secret agent who Jane believes took his own life.

The Bond films are referenced as well. To prepare for her mission, Jane is required to wear a dinner suit, drink vodka martinis (shaken, not stirred), and practise raising her eyebrows, reputedly in the manner of Roger Moore. Like the film Bond, Jane has a very active love life, though falls in love with one of the agents of G.E.O.R.G.I.E, a redhead called Bridget. There are gadgets, too, in the form of deadly lipsticks.

I enjoyed the book, though as with most of the longer Bond parodies, such as ALLIGATOR and (ahem) Devil May Care, the joke wears thin after a while. However, the characters are better drawn than they usually are in parodies, and Jane is interesting enough to deserve to appear in further adventures.

There have been numerous candidates for the first female James Bond, notably Modesty Blaise, but Jane Bond has better claim than most, having a believability that others lack (that's not to say that the plot is believable, which is far more fantastic than any plot of Fleming's). It is this credibility that means that the book is not so much about a 'gay Bond' than simply an entertaining spoof of familiar Bondian tropes.

To be fair, Bond's attitude to homosexuality, as suggested for instance by his discussion with Troop about 'intellectuals' in the the Secret Service, is reasonably progressive for the time (it should be remembered that homosexual acts in private were not decriminalised in the UK until 1967), and this no doubt reflects Fleming's own relatively liberal views. After all, some of Fleming's best friends were gay.

However, it is not the gay characters that have made the Bond novels easy targets for camp parodies (we could blame instead Bond's particular habits, for instance in relation to food, and the homoerotic quality of Bond being hit on the genitals with a carpet beater), of which Cyril Connolly's 'Bond Strikes Camp' and 'The Spy who Minced in from the Cold', by Stanley Reynolds are notable examples. A rather more thoughtful parody, however, is Kiss the Girls and Make Them Spy (Harper Collins, 2001), by Mabel Maney.

The novel, set in 1965, concerns an attempt by a secret organisation, the Sons of Britain Society, to depose the Queen and return the Duke of Windsor to the throne. Enter Her Majesty's Secret Service, whose officers serve to protect the Queen, and another mysterious organisation, the Greater European Organization of Radical Girls Inderdicting Evil (G.E.O.R.G.I.E.), which is populated by lesbians sworn to protect the world from destruction wrought by men. Curiously, though, both the Secret Service and G.E.O.R.G.I.E. appear to be oblivious to the plot to kidnap the Queen until it's in full swing.

Meanwhile, James Bond is on sick leave, having suffered a nervous breakdown. In order to preserve the reputation of the Secret Service and the belief that England's top agent is still on active duty, his sister, Jane, who looks very much like James, is blackmailed by the service to take James' place. Jane's mission is to receive a medal from the Queen without raising suspicion.

James Bond's absence is, I suspect, designed to avoid breaching copyright, and there are other changes in personnel; M become N, Miss Moneypenny becomes Miss Tuppenny (and, incidentally, the head of G.E.O.R.G.I.E), and, borrowing from the films, Q becomes X. The author is familiar with the Bond novels: Jane has an unruly comma of hair, as does James, there is reference to the 'powder vine', and it's revealed that Jane's handler, Agent Pumpernickel, or 001, has a S-shaped scar on his cheek, which was made by an enemy agent to mark him as a spy. The scar not only recalls the scar that Fleming's Bond has on his cheek, but also the knife cut in the form of an inverted M that Bond receives on the back of his hand in Casino Royale.

That said, the author doesn't stick rigidly to the 'facts' of Fleming's novels. The Secret Service in Mabel Maney's novel is usually referred to as Her Majesty's Secret Service, operates in England, and exists solely to protect the Queen, just as the US Secret Service is tasked with protecting the President. And, of course, family details are wrong. Apart from the sister we never knew about, James' mother is called Sylvia, and his father, James Bond Sr, was a secret agent who Jane believes took his own life.

The Bond films are referenced as well. To prepare for her mission, Jane is required to wear a dinner suit, drink vodka martinis (shaken, not stirred), and practise raising her eyebrows, reputedly in the manner of Roger Moore. Like the film Bond, Jane has a very active love life, though falls in love with one of the agents of G.E.O.R.G.I.E, a redhead called Bridget. There are gadgets, too, in the form of deadly lipsticks.

I enjoyed the book, though as with most of the longer Bond parodies, such as ALLIGATOR and (ahem) Devil May Care, the joke wears thin after a while. However, the characters are better drawn than they usually are in parodies, and Jane is interesting enough to deserve to appear in further adventures.

There have been numerous candidates for the first female James Bond, notably Modesty Blaise, but Jane Bond has better claim than most, having a believability that others lack (that's not to say that the plot is believable, which is far more fantastic than any plot of Fleming's). It is this credibility that means that the book is not so much about a 'gay Bond' than simply an entertaining spoof of familiar Bondian tropes.

Thursday, 3 November 2016

Spectre inspires the first Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City

In a blog about James

Bond's impact on culture, I could hardly fail to mention the Day of

the Dead parade, which was held in Mexico City on 29th October as

part of its annual Day of the Dead festival. As I describe in a previous post, the festival traditionally involves offerings of food

and drink to household ancestors, streets decorated with flowers,

market-stalls selling edible skulls, and graveside feasts. This was

the first year that a parade was held in the city. And the reason why it was held

was due to Spectre (2015).

While I have my

misgivings about the film – Blofeld revealed as Bond's

step-brother? The series could have done without that complication –

it is undeniably spectacular, and the Day of the Dead parade that

opens the film is up there with the best of the series' pre-title

sequences.

Lourdes Berho, the chief executive of the Mexico Tourist Board must have thought so too. 'We knew that this was going to generate a desire on the part of people here, in Mexicans and among tourists,' she told reporters, 'to come and participate in a celebration, a big parade.'

The thousands of people who came to view the parade saw performers in skeleton costumes and masks, floats bedecked with skeletons, and giant skeleton marionettes. Some of the participants wore costumes from the film itself. Others had costumes inspired by the film or wore more traditional costumes, such as those representing Aztec warriors.

This isn't the first time James Bond has had an impact on aspects of life beyond the normal scope of popular culture. The revolving restaurant on the summit of the Schilthorn in the Swiss Alps has been known as Piz Gloria ever since it appeared in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969). Maps of the region around Phuket in Thailand (well, Google maps, at least) officially record a small islet off Khao Phing Kan as James Bond Island, which formed part of Scaramanga's lair in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974).

Whether Spectre's impact on the Day of the Dead festival will be as lasting as Bond's impact on the the Schilthorn and Phuket has been remains to be seen. As David Agren reports in the Guardian, some commentators, among them the editor of Nexos magazine, Esteban Illades, took to social media to denounce the parade as populist stunt. Interestingly, though, the Guardian also reports that parades and processions have in fact been part of the festival for a some years now, even if in a relatively minor way.

What Spectre has done is given that emerging tradition a boost, and changed expectations about what the Day of the Dead festival entails. I certainly wouldn't be surprised to see the parade return next year, and indeed hear of similar parades being held elsewhere. (Look out for a parade near you!). More generally, the parade demonstrates how James Bond continues to have significance and relevance in the wider cultural environment. It may be a while yet before we hear of a Jason Bourne Island...

Thursday, 27 October 2016

A visit to the Aston Martin museum

Sometimes, one stumbles on places of interest to the James Bond fan quite unexpectedly. A few weeks ago I was driving through the south Oxfordshire countryside – actually on a tour with fellow Bond aficionado Tom Cull (who runs the brilliant Artistic Licence Renewed website) of Ian Fleming's childhood homes – when we saw a brown road sign for the Aston Martin museum. I hadn't noticed that sign before (I was to learn that it had only been put up in February this year) and in fact hadn't been aware of the museum's existence. Unfortunately, the museum was closed that day, but this week I had the chance to pay a visit.

The museum, run by the Aston Martin Heritage Trust, is located in the small village of Drayton St Leonard, near Wallingford. No wonder I didn't know the museum existed. Even following the brown sign and driving through the village, it's not exactly easy to find. I felt as though I was on a mission worthy of Bond as I had to stop a couple of times to consult the directions on the website (the sat nav will only get you so far). And to add to the Bondian air, Chinooks, presumably from nearby RAF Benson, were flying low overhead.

I eventually found the museum, which is housed in a magnificent medieval barn (itself worth the admission fee) built for the monks of Dorchester Abbey. The museum is small – the building shares its space with the offices and archive of the Aston Martin Owners Club – but what wonderful things it contains.

The cars change from time to time, and I was lucky enough to see (double oh) seven of them. These included a 1972 Aston Martin DBS, a prototype of the Vanquish (the model that appeared in Die Another Day in 2001), the Nimrod/Aston Martin racing car, the NRA/C2 004, which tore around Le Mans in 1982, and a full-scale ceramic and plastic model of the exclusive Aston Martin One-77, of which just 77 were built in 2008 and 2009.

There were more treasures around the edges of the barn. Display cases of trophies, medals and flags spoke of Aston Martin's many successes on the race track. Another case celebrated its drivers, among them the legendary Sir Stirling Moss (who takes his place in Bond lore as a character in one of Ian Fleming's unused television series treatments ('Murder on Wheels') and the basis of Lancy Smith in Anthony Horowitz's Trigger Mortis (2015)). Seeing the helmet and overalls worn by Stirling Moss during his time driving for Aston Martin was a thrill.

No collection of Aston Martin memorabilia is complete without reference to James Bond, and naturally part of a display case was devoted to toy cars, models and other representations of Bond's cars.

The museum staff were helpful and friendly, and I was privileged to be given something of a guided tour by one member of the trust, with whom I had an enjoyable discussion about cars and Bond and other things beside.

Like the cars themselves, the museum isn't large inside, but it's very well put together and endlessly fascinating. It's a must-see for any Bond fan.

The museum, run by the Aston Martin Heritage Trust, is located in the small village of Drayton St Leonard, near Wallingford. No wonder I didn't know the museum existed. Even following the brown sign and driving through the village, it's not exactly easy to find. I felt as though I was on a mission worthy of Bond as I had to stop a couple of times to consult the directions on the website (the sat nav will only get you so far). And to add to the Bondian air, Chinooks, presumably from nearby RAF Benson, were flying low overhead.

I eventually found the museum, which is housed in a magnificent medieval barn (itself worth the admission fee) built for the monks of Dorchester Abbey. The museum is small – the building shares its space with the offices and archive of the Aston Martin Owners Club – but what wonderful things it contains.

|

| Inside the Aston Martin museum |

There were more treasures around the edges of the barn. Display cases of trophies, medals and flags spoke of Aston Martin's many successes on the race track. Another case celebrated its drivers, among them the legendary Sir Stirling Moss (who takes his place in Bond lore as a character in one of Ian Fleming's unused television series treatments ('Murder on Wheels') and the basis of Lancy Smith in Anthony Horowitz's Trigger Mortis (2015)). Seeing the helmet and overalls worn by Stirling Moss during his time driving for Aston Martin was a thrill.

|

| A helmet worn by Stirling Moss |

|

| The James Bond display |

Like the cars themselves, the museum isn't large inside, but it's very well put together and endlessly fascinating. It's a must-see for any Bond fan.

Friday, 21 October 2016

Supersonic Buchan: Moonraker and John Buchan's The Three Hostages

While I’ve long maintained that the origin of James Bond owes more to American hardboiled thrillers by the likes of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett than it does to pre-Second World War literary clubland heroes, such as Bulldog Drummond and Richard Hannay, there is no denying that the third Bond novel, Moonraker (1955) is Ian Fleming at his most Buchan-esque.

I was reminded of this as I read the fourth Hannay adventure, The Three Hostages (1924). In the book, set after the First World War, Hannay is a retired army general eager for the quiet life at his Cotswold estate. Before long, though, he is persuaded by Macgillivray, who works for the Secret Service, to use his particular set of skills to help, unofficially, in the search for three individuals of note who have been kidnapped by a criminal gang.

Hannay has little to go on other than a piece of indifferent doggerel written by the mastermind behind the plot. The clue is enough, however, to take Hannay to one Dominick Medina, a extraordinarily handsome, clever and popular politician, the best shot in England and a poet to boot. Hannay initially seeks Medina's assistance, but realises, eventually, that Medina is the villain at the centre of the conspiracy.

In general terms, The Three Hostages and Moonraker cover similar ground. Both have home-grown plots that begin in the refined and exclusive surroundings of London's clubland. Indeed, Hannay and Bond first meet Medina and Moonraker's villain, Sir Hugo Drax, in gentlemen's clubs (the Thursday Club and Blades, respectively). The schemes of both villains' aim to strike at the heart of the British government and bring the country to its knees, reflecting the deep-seated hatred that Medina and Drax have for Britain.

The villains, too, are cut from a similar cloth. Both are adored by the public and, at least initially, by the books' heroes. When M asks if he's heard of Sir Hugo, Bond replies that 'you can't open a paper without reading something about him'. The man's a national hero, Bond adds, and continues to give a gushing account of Drax before pausing, 'almost carried away by the story of this extraordinary man.'

Hannay's rather smitten with his man as well, and has the same thought as Bond. 'You couldn't open a paper without seeing something about Dominick Medina', he tells us. Hannay's friend, Dr Greenslade considers Medina a great man, and judging by the papers, the whole world thinks so too. When Hannay meets Medina, he remarks on the attractiveness of the man, his easy-going personality, and admits to being fascinated by him and under his spell.

Hannay tells his best friend and co-adventurer, Sandy Arbuthnot, that Medina is 'the only fellow I ever heard of who was adored by women and liked by men', a line that has a curious echo in the phrase applied to Bond by Raymond Mortimer: 'James Bond is what every man would like to be, and what every woman would like between her sheets.'

Neither Bond nor Hannay are quick to suspect Drax and Medina of villainous intent, and in a way the idea that a powerful, seemingly altruistic, and charming man is beyond suspicion has endured in fiction, finding expression, for example, in the Bond films. In the film of Moonraker, when Bond takes M and the Minister of Defence to Drax's secret laboratory, the Minister is sceptical. 'I hope you know what you're doing, Bond', he says, 'I've played bridge with Drax.' And similarly, in A View To A Kill (1985) when Bond wonders if Zorin himself was responsible for an infiltration of Zorin Industries by the KGB, the Minister of Defence splutters, 'Max Zorin? Impossible. He's a leading French industrialist... with influential friends in the government.'

Drax can't compete with Medina for looks. Drax has facial scars from the war, and has protruding front teeth or a diastema that he attempts to hide by growing a luxurious moustache. But Medina isn't perfect either. Hannay notes that Medina's head 'was really round, the roundest head' he had ever seen. He continues that Medina was 'conscious of it and didn't like it, so took some pains to conceal it' with his hair. Oddly enough, the very round head would be a villainous trait in a Bond novel. In Live and Let Die, Mr Big is described as having 'a great football of a head, twice the normal size and very nearly round.'

One final shared trait worth mentioning is that both Drax and Medina are somehow 'other' by virtue of their foreignness or perceived foreignness, which to some extent explains their villainy. Drax is of course revealed to be German. Dominick Medina is English, but his name raises a question in Hannay's mind. 'I suppose he's some sort of Dago', he says to Greenslade. On meeting Medina, Hannay remarks that his face 'was very English, and yet not quite English.'

I wouldn't go as far as to say that Ian Fleming was influenced by The Three Hostages directly, but given their common traits or memes, Buchan's novel and Moonraker certainly inhabit the same cultural environment. Famously, one critic referred to Fleming as 'supersonic John Buchan'. In the case of Moonraker, I'm rather inclined to agree.

I was reminded of this as I read the fourth Hannay adventure, The Three Hostages (1924). In the book, set after the First World War, Hannay is a retired army general eager for the quiet life at his Cotswold estate. Before long, though, he is persuaded by Macgillivray, who works for the Secret Service, to use his particular set of skills to help, unofficially, in the search for three individuals of note who have been kidnapped by a criminal gang.

Hannay has little to go on other than a piece of indifferent doggerel written by the mastermind behind the plot. The clue is enough, however, to take Hannay to one Dominick Medina, a extraordinarily handsome, clever and popular politician, the best shot in England and a poet to boot. Hannay initially seeks Medina's assistance, but realises, eventually, that Medina is the villain at the centre of the conspiracy.

In general terms, The Three Hostages and Moonraker cover similar ground. Both have home-grown plots that begin in the refined and exclusive surroundings of London's clubland. Indeed, Hannay and Bond first meet Medina and Moonraker's villain, Sir Hugo Drax, in gentlemen's clubs (the Thursday Club and Blades, respectively). The schemes of both villains' aim to strike at the heart of the British government and bring the country to its knees, reflecting the deep-seated hatred that Medina and Drax have for Britain.

The villains, too, are cut from a similar cloth. Both are adored by the public and, at least initially, by the books' heroes. When M asks if he's heard of Sir Hugo, Bond replies that 'you can't open a paper without reading something about him'. The man's a national hero, Bond adds, and continues to give a gushing account of Drax before pausing, 'almost carried away by the story of this extraordinary man.'

Hannay's rather smitten with his man as well, and has the same thought as Bond. 'You couldn't open a paper without seeing something about Dominick Medina', he tells us. Hannay's friend, Dr Greenslade considers Medina a great man, and judging by the papers, the whole world thinks so too. When Hannay meets Medina, he remarks on the attractiveness of the man, his easy-going personality, and admits to being fascinated by him and under his spell.

Hannay tells his best friend and co-adventurer, Sandy Arbuthnot, that Medina is 'the only fellow I ever heard of who was adored by women and liked by men', a line that has a curious echo in the phrase applied to Bond by Raymond Mortimer: 'James Bond is what every man would like to be, and what every woman would like between her sheets.'

Neither Bond nor Hannay are quick to suspect Drax and Medina of villainous intent, and in a way the idea that a powerful, seemingly altruistic, and charming man is beyond suspicion has endured in fiction, finding expression, for example, in the Bond films. In the film of Moonraker, when Bond takes M and the Minister of Defence to Drax's secret laboratory, the Minister is sceptical. 'I hope you know what you're doing, Bond', he says, 'I've played bridge with Drax.' And similarly, in A View To A Kill (1985) when Bond wonders if Zorin himself was responsible for an infiltration of Zorin Industries by the KGB, the Minister of Defence splutters, 'Max Zorin? Impossible. He's a leading French industrialist... with influential friends in the government.'

Drax can't compete with Medina for looks. Drax has facial scars from the war, and has protruding front teeth or a diastema that he attempts to hide by growing a luxurious moustache. But Medina isn't perfect either. Hannay notes that Medina's head 'was really round, the roundest head' he had ever seen. He continues that Medina was 'conscious of it and didn't like it, so took some pains to conceal it' with his hair. Oddly enough, the very round head would be a villainous trait in a Bond novel. In Live and Let Die, Mr Big is described as having 'a great football of a head, twice the normal size and very nearly round.'

One final shared trait worth mentioning is that both Drax and Medina are somehow 'other' by virtue of their foreignness or perceived foreignness, which to some extent explains their villainy. Drax is of course revealed to be German. Dominick Medina is English, but his name raises a question in Hannay's mind. 'I suppose he's some sort of Dago', he says to Greenslade. On meeting Medina, Hannay remarks that his face 'was very English, and yet not quite English.'

I wouldn't go as far as to say that Ian Fleming was influenced by The Three Hostages directly, but given their common traits or memes, Buchan's novel and Moonraker certainly inhabit the same cultural environment. Famously, one critic referred to Fleming as 'supersonic John Buchan'. In the case of Moonraker, I'm rather inclined to agree.

Tuesday, 11 October 2016

Was Octopussy's clown chase inspired by Berlin Express (1948)?

The film of Octopussy suffers from something of an identity crisis. Part Cold War thriller, part old-fashioned comedy adventure, it tries to have its cake and eat it too, as it continues the more serious, Fleming-esque style that resumed with For Your Eyes Only, while returning to the Carry On-style antics of The Spy Who Loved Me or Moonraker. For all that, the film is hugely enjoyable, and I have a lot of time for it.

Admittedly James Bond in a gorilla suit does little to burnish the film's reputation, and some might baulk also at the idea of Bond in a clown suit. While the gorilla suit is probably a step too far, the film just about gets away with the clown-disguised spies. Both the clown chase at the beginning of the film and the scene in which Bond, dressed as a clown, attempts to diffuse the bomb hidden in the cannon in the circus big-top, are uncanny and suspenseful and have more than a touch of Hitchcock about them.

What is especially interesting about the clown chase sequence, in which 009, in possession of a Fabergé egg, tries to escape from East Berlin, is that it is not completely a new idea, but is very similar in structure to a sequence in a much earlier espionage drama, Berlin Express, directed by Jacques Tourneur and released in 1948.

In that film, we follow a group of international travellers on a train to Berlin. One of the party is a Dr Bernhardt, who has been instrumental in brokering a settlement concerning the post-war reconstruction of Germany. There are sinister forces against him, though, and on the train his enemies make an attempt on his life. The assassination plot fails, but in Frankfurt, where the train is forced to stop, Dr Bernhardt is kidnapped. Four of his fellow passengers, among them Robert Ryan, who plays an American traveller, help a US army major to search the city for him.

One of the gang's hideouts is a beer-hall. There is a cabaret there, and among the entertainers is a clown called Perrot. He is also one of the gang, but before he leaves the hall to go to an underground warehouse or vault where Dr Bernhardt is hidden, he is knocked out by Hans Schmidt, a German agent who has been assigned by the US War Department to protect Dr Bernhardt. Schmidt takes the place of the clown, costume and all, and gains access to the vault.

At the vault, Schmidt confirms that Dr Bernhardt is there and tries to sneak out to inform the US authorities. At that moment, Perrot enters, and the rest of the gang realise that Schmidt is an imposter. In the sequence that follows, we can draw several parallels with 009's flight in Octopussy.

Schmidt runs up a staircase to the exit, but is shot in the back, just as 009 receives a knife in the back from Grischa.

As Schmidt makes his way back to the beer-hall, he is pursued by two of the gang members. At one point he conceals himself behind the rubble of the bombed-out city. As he makes another run for it, his cloak gets caught and drops to the floor. Similarly, 009 is pursued through the woods of East Berlin by two men, Mischa and Grischa, and loses his hat when it catches on a branch of a tree.

Schmidt arrives at the beer-hall, presumably where he knows he can make contact with the US major, and staggers on to the stage. He sees the major, and starts to walk through the crowd of patrons towards him. 009 arrives at the British embassy and staggers towards the ambassador's room.

Just before reaching the major, Schmidt twists in pain and crashes to the floor, eliciting a scream from one of the patrons. In Octopussy, 009 smashes through the french windows, eliciting a gasp from the ambassador's wife, and crashes to the floor. Schmidt remains alive for long enough to tell the US army major where Dr Bernhardt is being kept. 009 is dead, but in releasing the egg, allowing it to roll to the ambassador, he has imparted vital information.

The similarities between the 009 and Schmidt sequences are striking. It is uncertain whether Octopussy's screenwriters, George MacDonald Fraser, Richard Maibaum and Michael G Wilson, or indeed the director John Glen, whose experience on the set of The Third Man (1949), a film contemporary with Berlin Express and of the same genre, informed scenes in his later film, The Living Daylights (1987), were inspired by the earlier clown sequence. But even if the similarities are coincidental, the 1948 film shows that there is a precedent for the use of clown-disguised spies in Octopussy. The idea is not such a ludicrous one after all.

Admittedly James Bond in a gorilla suit does little to burnish the film's reputation, and some might baulk also at the idea of Bond in a clown suit. While the gorilla suit is probably a step too far, the film just about gets away with the clown-disguised spies. Both the clown chase at the beginning of the film and the scene in which Bond, dressed as a clown, attempts to diffuse the bomb hidden in the cannon in the circus big-top, are uncanny and suspenseful and have more than a touch of Hitchcock about them.

What is especially interesting about the clown chase sequence, in which 009, in possession of a Fabergé egg, tries to escape from East Berlin, is that it is not completely a new idea, but is very similar in structure to a sequence in a much earlier espionage drama, Berlin Express, directed by Jacques Tourneur and released in 1948.

In that film, we follow a group of international travellers on a train to Berlin. One of the party is a Dr Bernhardt, who has been instrumental in brokering a settlement concerning the post-war reconstruction of Germany. There are sinister forces against him, though, and on the train his enemies make an attempt on his life. The assassination plot fails, but in Frankfurt, where the train is forced to stop, Dr Bernhardt is kidnapped. Four of his fellow passengers, among them Robert Ryan, who plays an American traveller, help a US army major to search the city for him.

One of the gang's hideouts is a beer-hall. There is a cabaret there, and among the entertainers is a clown called Perrot. He is also one of the gang, but before he leaves the hall to go to an underground warehouse or vault where Dr Bernhardt is hidden, he is knocked out by Hans Schmidt, a German agent who has been assigned by the US War Department to protect Dr Bernhardt. Schmidt takes the place of the clown, costume and all, and gains access to the vault.

At the vault, Schmidt confirms that Dr Bernhardt is there and tries to sneak out to inform the US authorities. At that moment, Perrot enters, and the rest of the gang realise that Schmidt is an imposter. In the sequence that follows, we can draw several parallels with 009's flight in Octopussy.

Schmidt runs up a staircase to the exit, but is shot in the back, just as 009 receives a knife in the back from Grischa.

|

| Both Schmidt and 009 get it in the back |

|

| Both Schmidt and 009 lose garments in the chase |

|

| Schmidt and 009 stagger to their goals |

|

| Both Schmidt and 009 crash to the floor but impart the vital information |

Wednesday, 5 October 2016

The hoary euphemism: James Bond of the Ministry of Defence

|

| Image: Wikipedia |

What also caught my eye was Tom Marcus' description of how officers account for the period spent in MI5 when they've left the service and are applying for jobs; naturally former agents remain bound by the Official Secrets Act and must invent plausible cover stories. He told the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme that “some people come up with a Ministry of Defence cover story, but trying to explain the skills you say you have for a made-up story just unravels – and I wouldn't feel comfortable doing that.”

I was interested to read this, because the Ministry of Defence cover story is what James Bond of the novels uses. The first occasion seems to be in Diamonds are Forever (1956, chapter 3), when Assistant Commissioner Vallance introduces Bond to Inspector Dankwaerts as Commander Bond of the Ministry of Defence. In The Spy who Loved Me (1962, chapter 15), Bond gives the Ministry of Defence as his address in a letter to Vivienne Michel.

There are two references in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963). At the College of Arms, Bond tells Griffon Or that he's from the Ministry of Defence (chapter 6), and we learn that Sable Basilisk thought Bond was vaguely employed by the Ministry of Defence (chapter 8).

In his obituary of Bond in You Only Live Twice (1964, chapter 21), M identifies Bond as an officer of the Ministry of Defence, as does the Jamaican police commissioner in The Man with the Golden Gun (1965, chapter 16).

It's in the short story 'Octopussy' that Fleming describes the Ministry of Defence cover, used by Bond when greeting Major Dexter Smythe, as 'the hoary euphemism' for the Secret Service. In another short story, 'The Property of a Lady', Bond tells Fabergé expert Kenneth Snowman that he's from the Ministry of Defence.

In light of Tom Marcus' account, these occurrences raise some interesting points. One is that the Ministry of Defence cover story is a legitimate one, and its use in the Bond books may well reflect a reality of British Intelligence. In other words, the use of the Ministry of Defence as a front had currency when Ian Fleming was writing and remains current now.

Another point is that most Ministry of Defence references appear in the final few books. There is just one occurrence in the first nine books, but in the final five, there is at least one reference in each. It's not obvious why this should be the case, but possibly Fleming used the Ministry of Defence trope or meme to add authenticity to the stories. Also, with each successive use of the meme, the chances that Fleming would use it again in the next book increased.

Monday, 3 October 2016

The tradition of the operational mix-up

|

| First edition cover by Richard Chopping, published by Jonathan Cape |

Bond surmises that Campbell was following a lead of his own and had no knowledge of Bond's mission. “Typical of the sort of balls-up that over-security can produce!”, Bond concludes, but he does the only thing that an agent can do in such circumstances: deny Campbell and leave him to his fate.

The operational mix-up is something of a standard trope, and Ian Fleming could have drawn on several examples from spy and detective fiction. One example can be found in Dennis Wheatley's short story Espionage, published in Mediterranean Nights (1942). British secret service agent Rowley Thornton is travelling by train to St Tropez, and becomes suspicious about a German women, Fraulein Lisabetta, who is sharing his compartment (the story is set between the world wars). Suspecting that Lisabetta has taken possession of secret blue prints for a new fighter plane stolen by a German agent, Rowley goes after her and plans to have her hotel room searched or, if necessary, have her searched.

However, it transpires that Lisabetta is herself a British agent, who has inveigled the blue prints from the German agent. As Rowley later reflects, “It's one of the rules of the service that even if your own side gets up against you through ignorance you must never show your hand until your job is done.”

This rule of never showing your hand is also evident in Peter Cheyney's Never a Dull Moment (1942). FBI agent Lemmy Caution is in England, investigating the disappearance of a woman, Julia Wayles. He suspects that American gangster Maxie Schribner has something to do with her disappearance and is talking to Schribner at his English residence.

When another gangster, Rudolf, enters the house, Caution “almost gets heart disease”. Though purporting to be one of Schribner's associates, Rudolf is actually a fellow FBI agent, Charlie Milton, working under cover. A few words from Milton prevent Caution from giving the game away, but unfortunately for Caution, Milton also maintains his cover by “smacking [him] one across the kisser that makes [his] teeth bounce.” Caution is out for the count and comes to in the cellar waiting to be thrown in the river.

With these examples in mind, we can see that Ian Fleming continued the tradition of the operational mix-up. James Bond sticks to the rule of never showing your hand until the job is done, but finds that it is a rule that can have harsh consequences.

Friday, 23 September 2016

Why is the head of a central bank like James Bond?

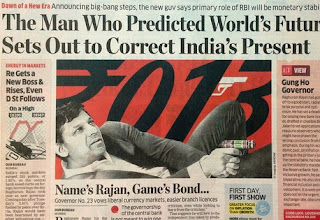

You don't often hear of a banker being compared to James Bond; a Bond villain, perhaps, but not Bond. But back in June, Raghuram Rajan, formerly the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (he stepped down earlier this month), was dubbed James Bond by the country's media.

The James Bond tag hit the world's headlines when he was depicted as 007 in an image published in India's Economic Times. The illustration, based on a poster used for Skyfall, showed Rajan with gun poised, ready to defend India's currency (the gun is covered with rupees). The caption below the illustration read 'Name's Rajan, Game's Bond'. Rajan has also been called 'Bond of Mint Street', and may have played on this when he once told reporters that 'My name is Rajan and I do what I do.'

What had Raghuram Rajan done to gain such an accolade? According to a profile of Rajan in the Economic Times, he enjoyed notable success as governor. He strengthened the rupee, cleaned up India's banks, brought an academic perspective to the job, was firm with interest rates, and gained a huge popular following. It seems that these successes gave rise to the perception that Rajan was dynamic (the Economist Times also called him the 'gung ho governor'), clever, and cool (both with regard to interest rates and criticism within the sector), and it is these qualities that linked him to Bond.

Had he known that banking could be so adventurous and action-packed, perhaps Ian Fleming would have been tempted to give his short banking career (he spent a year at merchant bankers, Cull and Co.) a longer run!

The James Bond tag hit the world's headlines when he was depicted as 007 in an image published in India's Economic Times. The illustration, based on a poster used for Skyfall, showed Rajan with gun poised, ready to defend India's currency (the gun is covered with rupees). The caption below the illustration read 'Name's Rajan, Game's Bond'. Rajan has also been called 'Bond of Mint Street', and may have played on this when he once told reporters that 'My name is Rajan and I do what I do.'

|

| Raghuram Rajan as Bond, according to the Economic Times |

Had he known that banking could be so adventurous and action-packed, perhaps Ian Fleming would have been tempted to give his short banking career (he spent a year at merchant bankers, Cull and Co.) a longer run!

Monday, 19 September 2016

Is Ian Fleming in the Cheyney class?

Peter Cheyney was a British author of espionage stories and American-style hard-boiled detective fiction. Largely forgotten and unread today, he enjoyed huge success between the 1930s and 1950s, when his work was published; according to Fergus Fleming, Cheyney sold over 1,500,000 copies of his books in 1946. It is little wonder, then, that in the early days of his Bond career, Ian Fleming aspired to what he termed 'the Cheyney class', wishing to emulate Cheyney's success and appeal.

We learn this from the superb collection of Ian Fleming's letters, edited by his nephew Fergus and published last year by Bloomsbury. Fleming's aspiration is revealed in a letter to Jonathan Cape in 1953 concerning Live and Let Die. By the time of From Russia, with Love, published in 1957, Fleming's view of Cheyney had changed. In a letter to Wren Howard of Jonathan Cape, Fleming wrote that a proposed comic strip for the Express risked his work descending 'into the Cheyney class'. What was once emulated for its style and popularity was now regarded as inferior and low-brow.

Fleming's later view of Cheyney seems to have continued unchanged for the remainder of his Bond career. It is telling that in interviews given in the early 1960s, Fleming listed, among others, Chandler, Hammett and Oppenheim as influences, but there is no mention of Cheyney. Reading Peter Cheyney now, it is not difficult to understand why Cheyney has not stood the test of time and why Fleming thought his work a cut above the Cheyney class.

Peter Cheyney's 1942 novel, Never a Dull Moment, one of a number of books that feature FBI detective Lemmy Caution, is a case in point. The narrative takes place in England during the Second World War (Cheyney's novels have contemporary settings). Caution is on leave in Scotland, but is requested by the FBI to go to London and investigate the disappearance of an American woman, Julia Wayles. In the course of his enquiries, he discovers a gang of American gangsters working in England for the Germans as a fifth column.

The novel is for the most part exciting and fast-paced, and superficially there are similarities with the Bond novels. The names of Cheyney's femme fatales, such as Dodo Malendas, are as exotic-sounding as those of Fleming's heroines. Caution is tough with the villains and attractive to women, and he'd more than match Bond in his alcohol consumption. We even get a 'Caution, Lemmy Caution' when Caution introduces himself to another character.

As with the Philip Marlowe novels, the Lemmy Caution novels are written in the first-person. Some of the lines come close to Chandler quality (“He lets go a gasp like a steam whistle. I take advantage of the pause in hostilities to punch him in the belly hard.”), but some of the scenes and descriptions are repetitive, and I found that the narrative, rendered in a vernacular style, became tedious to read after a while. To the modern reader, the book might best be regarded as sub-Chandler or, more generally, a parody of a hard-boiled thriller.

Cheyney's espionage writing is rather more conventional. For example, his short story, 'The Double Double-Cross' is a nice little tale about a plan to bring a halt to the activities of the seductive Roanne Lucrezia Loranoff, a Russian aristocrat, émigrée and spy. The story sits comfortably alongside any spy story of the time, but in no obvious sense could it be considered a forerunner of Bond.

That said, another of Cheyney's espionage stories is Dark Duet (1942), which Raymond Chandler considered to be Cheyney's one good book, telling Ian Fleming so in a letter in 1955. One of the characters in the book is called Hildebrand. Three years after Chandler's letter, Hildebrand would crop up again in the title of one of Fleming's short stories.

So is Ian Fleming in or out of the Cheyney class? In my view, definitely out, being some distance above it. But that is not to say that Peter Cheyney doesn't deserve to be read. While his Lemmy Caution novels can be hard-going to the modern reader, Cheyney's espionage stories are a better read and earn their place in the development of spy fiction.

Reference:

Fleming, F (ed.), 2015 The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming's James Bond Letters, Bloomsbury

We learn this from the superb collection of Ian Fleming's letters, edited by his nephew Fergus and published last year by Bloomsbury. Fleming's aspiration is revealed in a letter to Jonathan Cape in 1953 concerning Live and Let Die. By the time of From Russia, with Love, published in 1957, Fleming's view of Cheyney had changed. In a letter to Wren Howard of Jonathan Cape, Fleming wrote that a proposed comic strip for the Express risked his work descending 'into the Cheyney class'. What was once emulated for its style and popularity was now regarded as inferior and low-brow.

Fleming's later view of Cheyney seems to have continued unchanged for the remainder of his Bond career. It is telling that in interviews given in the early 1960s, Fleming listed, among others, Chandler, Hammett and Oppenheim as influences, but there is no mention of Cheyney. Reading Peter Cheyney now, it is not difficult to understand why Cheyney has not stood the test of time and why Fleming thought his work a cut above the Cheyney class.

Peter Cheyney's 1942 novel, Never a Dull Moment, one of a number of books that feature FBI detective Lemmy Caution, is a case in point. The narrative takes place in England during the Second World War (Cheyney's novels have contemporary settings). Caution is on leave in Scotland, but is requested by the FBI to go to London and investigate the disappearance of an American woman, Julia Wayles. In the course of his enquiries, he discovers a gang of American gangsters working in England for the Germans as a fifth column.

The novel is for the most part exciting and fast-paced, and superficially there are similarities with the Bond novels. The names of Cheyney's femme fatales, such as Dodo Malendas, are as exotic-sounding as those of Fleming's heroines. Caution is tough with the villains and attractive to women, and he'd more than match Bond in his alcohol consumption. We even get a 'Caution, Lemmy Caution' when Caution introduces himself to another character.

As with the Philip Marlowe novels, the Lemmy Caution novels are written in the first-person. Some of the lines come close to Chandler quality (“He lets go a gasp like a steam whistle. I take advantage of the pause in hostilities to punch him in the belly hard.”), but some of the scenes and descriptions are repetitive, and I found that the narrative, rendered in a vernacular style, became tedious to read after a while. To the modern reader, the book might best be regarded as sub-Chandler or, more generally, a parody of a hard-boiled thriller.

Cheyney's espionage writing is rather more conventional. For example, his short story, 'The Double Double-Cross' is a nice little tale about a plan to bring a halt to the activities of the seductive Roanne Lucrezia Loranoff, a Russian aristocrat, émigrée and spy. The story sits comfortably alongside any spy story of the time, but in no obvious sense could it be considered a forerunner of Bond.

That said, another of Cheyney's espionage stories is Dark Duet (1942), which Raymond Chandler considered to be Cheyney's one good book, telling Ian Fleming so in a letter in 1955. One of the characters in the book is called Hildebrand. Three years after Chandler's letter, Hildebrand would crop up again in the title of one of Fleming's short stories.

So is Ian Fleming in or out of the Cheyney class? In my view, definitely out, being some distance above it. But that is not to say that Peter Cheyney doesn't deserve to be read. While his Lemmy Caution novels can be hard-going to the modern reader, Cheyney's espionage stories are a better read and earn their place in the development of spy fiction.

Reference:

Fleming, F (ed.), 2015 The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming's James Bond Letters, Bloomsbury

Sunday, 11 September 2016

Jaguar evokes James Bond in its advertising

Jaguar, the car manufacturer, is no stranger to the world of James Bond. Last year in Spectre, we saw Oberhauser's goon, Mr Hinx, put Jaguar's concept car, the C-X75, through its paces on the streets of Rome. And in Die Another Day (2001), Zao battles Bond and the ice in a Jaguar XKR. We must wait until the next Bond film (whenever that will be) to find out whether Jaguar will make another appearance, but in the meantime, the spirit of Bond lives on in Jaguar's advertising.

The Art of Performance campaign, which promotes the Jaguar XE, is currently doing the rounds on British television (see the advert on my Licence to Cook Facebook page). In the advert, the car speeds (in controlled conditions) through the streets of central London. We see close-ups of the car before it zooms through a tunnel and comes out on to Westminster Bridge in view of the London Eye and Queen Elizabeth Tower.

The locations naturally evoke the final part of Spectre, particularly the tunnel in which M's car is rammed and Bond kidnapped, and the denouement on Westminster Bridge (an association helped by the Bondian music that accompanies the advert). To some extent, the advert also recalls the beginning of the pre-title sequence of Quantum of Solace, which, with its seductive glimpses of Bond's Aston Martin before the shooting starts, could almost be a car advert itself.

Another of Jaguar's campaigns also has distinct Bond-like qualities. The 2014 Art of Villainy commercial showcased the Jaguar F-type coupé and starred Tom Hiddleston, who, in the advert, reveals the essential characteristics of a villain (style, razor-sharp wit, attention to detail, and the means to stay one step ahead, among others) before tearing through the streets of London. (For this villainous act, the advert was banned by the UK's Advertising Standards Authority, who judged that it promoted dangerous driving). The advert made the car look good, of course, but could also be viewed as Hiddleston's audition for a Bond villain (if not Bond himself).

There's more Bond-like villainy in a 2014 advert starring Nicolas Hoult. If Tom Hiddleston is Blofeld, Nicolas Hoult is Q gone bad. In the commercial for the Jaguar XE, we see Hoult descend into his innovation lab (passing through a shark-infested pool) and explain, in what could be the antithesis of a typical Q briefing, what every mastermind needs in terms of automative technology to help them achieve world domination.

All three adverts are redolent of the James Bond films, and use memes closely associated with Bond, such as the urbane, sophisticated villain, iconic landscapes, the Q-like character, and buttons and switches inside the car that bring to mind gadgets and ejector seats. The adverts were not made with reference to any specific Bond product or film, but nevertheless depend on them. Even after half a century, James Bond continues to have significant traction in the world of advertising.

The Art of Performance campaign, which promotes the Jaguar XE, is currently doing the rounds on British television (see the advert on my Licence to Cook Facebook page). In the advert, the car speeds (in controlled conditions) through the streets of central London. We see close-ups of the car before it zooms through a tunnel and comes out on to Westminster Bridge in view of the London Eye and Queen Elizabeth Tower.