The identification of this period as a golden age is contentious – others would argue that that period belonged to the likes of John Buchan, Sapper, Peter Cheyney, and E Phillips Oppenheim – but there's no denying that the twenty year period saw an explosion of British thriller writers (many influenced by Ian Fleming or more generally the success of James Bond) who would dominate the thriller market across the world.

For me, the book gave me a sense of nostalgia. Not that I read any of these books at the time. Being born in the 1970s, I was too young, but some of the books that Mike Ripley mentions were on the bookshelves at home, among them Eric Ambler's The Levanter, John le Carré's Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (or was it Smiley's People?), and When Eight Bells Toil by Alistair MacLean. Such thrillers seeped into my consciousness at an early age.

Later, I began collecting thrillers, mainly published in the mid/late 1960s, that attempted to fill the void left by Ian Fleming, their heroes often being described on the back cover as the new James Bond or even better than James Bond (as if that were possible). Many of these are discussed by Mike Ripley too, such as DIECAST by John Michael Brett, Sergeant Death by James Mayo, and Where the Spies Are by James Leasor.

|

| Some of Bond's many rivals |

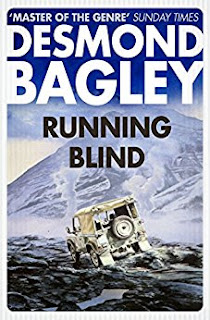

Running Blind is a Cold War thriller than falls somewhere between the realistic environment of George Smiley and the more fantastic world of James Bond. In the novel, former British agent Alan Stewart makes a routine visit to Iceland, where his girlfriend lives, but is met by another agent, who persuades him to deliver a package. When an attempt is made on his life, he realises he's been set up, forcing him to go on the run across Iceland's volcanic terrain, pursued by Russian, British, and American agents.

It's an exciting read, and while it's rather different to the James Bond books (except, maybe, John Gardner's Nobody Lives for Ever), the influence of Ian Fleming, or indeed the James Bond films, is not far away. There's a moment when Alan Stewart enters the room of Slade, a British agent whom Stewart suspects of having gone over to the Russians. Stewart looks out for a trick of the trade – hairs dabbed with saliva and stuck across the doors of the wardrobe that would be dislodged if the doors were opened.

A device of a similar nature is described in Casino Royale. When James Bond returns to his hotel room at Royale-les-Eaux, he inspects the hairs lodged in the drawer of the writing desk to make sure the drawer hadn't been opened. It's possible, though, that Desmond Bagley had been thinking of the film version of Dr No, in which Bond dabs a hair with saliva and sticks it across the doors of his wardrobe.

|

| James Bond takes precautions |

I expect that Running Blind will be the first of many thrillers from the 'golden age' that I'll discover and rediscover thanks to Mike Ripley's Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, and along the way be reminded (as if I needed reminding) of the enormous influence that Ian Fleming's work has had on thriller and spy fiction. As Mike Ripley notes, Casino Royale wasn't so much the spy novel that ended all spy novels, but the novel that launched many more.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.