In the second volume of Best Secret Service Stories, published in 1965, editor John Welcome devotes much of his introduction to Ian Fleming, who died the previous year. Welcome is generous and fulsome in his praise for Fleming's work. His books, Welcome writes, “were all beautifully written by an intelligence far above the ordinary.” “Fleming could write anyone else operating in this [the spy] genre clean off the page.” “Fleming had...in abundance the three essentials of a writer in this genre – pace, conviction and a compulsive readability.”

You won't hear any argument to the contrary from me, but Welcome's introduction is by no means a hagiography; Welcome acknowledges that there are considerable debts to Fleming's literary ledger. One of these, in Welcome's view, is Fleming's skill as a short story writer. “This was an aspect of the art of writing,” Welcome suggests, “in which [Fleming] was almost wholly at sea. Virtually all of the published short stories are misfires.” (It should be noted that at the time of publication, John Welcome had not seen Octopussy and The Living Daylights.)

Contrast this view with that of thriller writer Robert Ryan, who suggests in his introduction to the 2006 Penguin edition of Octopussy and The Living Daylights that “as with Sherlock Holmes... Bond was at his best in the shorter adventures,” and that Fleming “was a short story/novella man at heart.”

There is usually a tendency for books or films poorly received at the time of publication or release to acquire classic and cherished status simply with the passage of time (there's hope for Die Another Day yet). After reading Welcome's and Ryan's very different opinions, I wondered if this were the case with Fleming's short stories, but a quick survey of critical opinion suggests that Welcome is somewhat out on a limb.

In The James Bond Dossier (1965), Kingsley Amis thought 'From a View to a Kill' ingenious, 'Risico' well written, and 'The Hildenbrand Rarity' effective, while The Guardian thought the For Your Eyes Only collection better than the novels. Not to say that all critics were effusive. Philip Larkin thought that, unlike Sherlock Holmes, James Bond “does not fit snugly into the short story length.”

For my money, I'm with Robert Ryan – I think that Ian Fleming's short stories represent some of his best writing. 'Octopussy', 'From a View to a Kill', 'The Hildebrand Rarity' and 'The Living Daylights' are for me particular highlights, being full of thrills, insights into Bond, wonderful descriptions, and some delicious turns of phrase. It's a travesty that the first two of those still haven't been faithfully adapted for the screen. I would like to have seen more short stories from Fleming, and now that Fleming's unrealised TV treatments are reaching the page, perhaps one day I will.

Reference:

Chancellor, H, 2005 James Bond: The Man and his World: The Official Companion to Ian Fleming's Creation, John Murray, London

Saturday, 11 February 2017

Friday, 3 February 2017

Brazilian adventures: The Lost City of Z and Peter Fleming

Fans of the work of Ian Fleming's brother, Peter, might be interested in an upcoming film, The Lost City of Z, which tells the true story of the explorer Colonel Fawcett, who, in 1925, led an expedition deep into the Amazonian jungle to search for a fabled city of a lost civilisation. Fawcett and the rest of the expedition were never seen again, and Fawcett's fate was soon shrouded in mystery.

If the film proves to be a great success, and there's a clamour for a sequel, then the film-makers would do well to turn to Peter Fleming's 1933 book, Brazilian Adventure, in which Peter recounts the trials and tribulations of his own expedition into the Amazon to discover what had happened to Colonel Fawcett.

Peter and the other members of the expedition got no closer to solving the mystery, and, as if struck by a curse of the earlier explorer, saw more than their fair share of hardships and disaster. Along the way, they stumbled into a revolution in São Paulo, fell out with the expedition leader, Captain John Holman (largely identified as Major George Pingle in Peter's book), who had little interest in the search for Fawcett, hacked their way through impenetrable jungle, had so few provisions that they survived mainly on what they could hunt and forage, encountered alligators and piranhas, organised the evacuation of an expedition member who went down with blood poisoning, and, on deciding that they could go no further, faced a thousand-mile trek back to civilisation, all the time racing against Holman, who had the money and boat tickets.

As for what happened to Colonel Fawcett (spoiler alert), Peter accepted that Fawcett is likely to have died at the hands of the Suyá tribe, and if by some remote chance he had been alive at the time of Peter's expedition, he must have gone mad.

Peter Fleming's Brazilian adventure is every bit as thrilling as Fawcett's own, and is compelling, hilarious, and wonderfully evocative of the land and the people Peter met. If any cinema-goer, having watched The Lost City of Z (released in March), is wondering what happened next, I recommend they pick up a copy of Peter's book. And you never know, it might be coming to a cinema near you.

|

| Poster for The Lost City of Z, exclusively revealed by Empire |

Peter and the other members of the expedition got no closer to solving the mystery, and, as if struck by a curse of the earlier explorer, saw more than their fair share of hardships and disaster. Along the way, they stumbled into a revolution in São Paulo, fell out with the expedition leader, Captain John Holman (largely identified as Major George Pingle in Peter's book), who had little interest in the search for Fawcett, hacked their way through impenetrable jungle, had so few provisions that they survived mainly on what they could hunt and forage, encountered alligators and piranhas, organised the evacuation of an expedition member who went down with blood poisoning, and, on deciding that they could go no further, faced a thousand-mile trek back to civilisation, all the time racing against Holman, who had the money and boat tickets.

|

| Brazilian Adventure (Cape, 1933) |

Peter Fleming's Brazilian adventure is every bit as thrilling as Fawcett's own, and is compelling, hilarious, and wonderfully evocative of the land and the people Peter met. If any cinema-goer, having watched The Lost City of Z (released in March), is wondering what happened next, I recommend they pick up a copy of Peter's book. And you never know, it might be coming to a cinema near you.

Friday, 27 January 2017

Mightier than the sword: the trick pen in the Bond films and beyond

The humble pen makes an ideal gadget for the spy. It's small, it can be discreetly concealed in the pocket, but arouses no suspicion when taken out, and can be modified to house all sorts of devices. It's no wonder the pen-based gadget has been seen a few times in the James Bond films.

In Moonraker (1979), we learn that a deadly-tipped pen, which Bond finds on Holly Goodhead's hotel dressing table, is standard CIA issue. In Octopussy (1983), a fountain pen made by Mont Blanc is multi-functional, containing a highly concentrated mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid ('wonderful for poison pen letters') and an earpiece to a listening device. Coincidentally, Never Say Never Again, the rival Bond film released in the same year, also includes a fountain pen among its gadgets; that one is able to release an explosive charge.

The explosive pen was reinvented for GoldenEye (1995) and used to great dramatic and comic effect. The film featured a Parker Jotter ballpoint, which contains a class-four grenade that is armed with three clicks of end button and disarmed with three more. (I've never looked at a ballpoint pen in quite the same way since, and on idly clicking the end of one, often wonder whether it's about to go off.)

Curiously, a very similar device featured in Wild Geese II, released ten years earlier. In that film, Michael (played by John Terry, who would become Felix Leiter in The Living Daylights), a member of the organisation that has hired mercenaries to spring Rudolf Hess from prison, is given an explosive ballpoint pen. Like GoldenEye's pen, it's armed by clicking the end, though has a longer fuse (40 seconds, as opposed to four seconds).

These gadgets may seem fantastic, but there's a long tradition of adapting pens for secret use in the real world of espionage. The Second World War saw teams of boffins create an ingenious array of gadgets from ordinary objects. Charles Fraser-Smith, often claimed to be the inspiration for the character of Q (which seems fanciful, given that there was no such character in the Bond books), was responsible, among many other devices, for a fountain pen that could conceal documents.

The use of trick pens continued into the Cold War. In an interview with Ian Fleming published in 1965, Bernard Hutton, an expert on Soviet espionage, revealed how Soviet spies used dynamite-filled fountain pens for the purpose of assassination.

The gadget-filled pen is so well established in espionage lore that today the idea might seem hackneyed. This may explain Q's comment to Bond in Skyfall (2012): 'Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don't really go in for that any more.'

And the idea of trick pens has been subverted in other films. During the tank sequence in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Professor Henry Jones (Sean Connery) shakes off a German soldier – who then stumbles and knocks himself out – by squirting ink from his fountain pen into the soldier's face. More recently, in The Bourne Identity (2002), Jason Bourne uses a biro as a stabbing weapon.

In a way dismissing the notion of the sort of gadgets seen in the Bond films, both cases demonstrate that the ordinary can become extraordinary; you don't need to fill a pen with explosives to turn it into a deadly weapon.

In Moonraker (1979), we learn that a deadly-tipped pen, which Bond finds on Holly Goodhead's hotel dressing table, is standard CIA issue. In Octopussy (1983), a fountain pen made by Mont Blanc is multi-functional, containing a highly concentrated mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid ('wonderful for poison pen letters') and an earpiece to a listening device. Coincidentally, Never Say Never Again, the rival Bond film released in the same year, also includes a fountain pen among its gadgets; that one is able to release an explosive charge.

The explosive pen was reinvented for GoldenEye (1995) and used to great dramatic and comic effect. The film featured a Parker Jotter ballpoint, which contains a class-four grenade that is armed with three clicks of end button and disarmed with three more. (I've never looked at a ballpoint pen in quite the same way since, and on idly clicking the end of one, often wonder whether it's about to go off.)

|

| Q demonstrates the 'pen grenade' in GoldenEye |

|

| Mercenary John Haddad demonstrates the 'pen grenade' in Wild Geese II |

|

| One of Charles Fraser-Smith's gadgets |

The use of trick pens continued into the Cold War. In an interview with Ian Fleming published in 1965, Bernard Hutton, an expert on Soviet espionage, revealed how Soviet spies used dynamite-filled fountain pens for the purpose of assassination.

The gadget-filled pen is so well established in espionage lore that today the idea might seem hackneyed. This may explain Q's comment to Bond in Skyfall (2012): 'Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don't really go in for that any more.'

And the idea of trick pens has been subverted in other films. During the tank sequence in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Professor Henry Jones (Sean Connery) shakes off a German soldier – who then stumbles and knocks himself out – by squirting ink from his fountain pen into the soldier's face. More recently, in The Bourne Identity (2002), Jason Bourne uses a biro as a stabbing weapon.

In a way dismissing the notion of the sort of gadgets seen in the Bond films, both cases demonstrate that the ordinary can become extraordinary; you don't need to fill a pen with explosives to turn it into a deadly weapon.

Friday, 20 January 2017

Steampunk Bond: Another Bond villain from the pages of Jules Verne

Regular readers of this blog may have noticed that I'm an avid reader of Jules Verne's novels. The connections between Jules Verne and James Bond may seem remote, but there are things in common. In an earlier post, I suggested that Robur the Conqueror, the villain in Jules Verne's 1904 novel, Master of the World, is a prototype Bond villain, and there's another strangely familiar villain in another of Verne's 'Voyages Extraordinaires', Facing the Flag (1896).

Enter the mysterious Count d'Artigas, who's also keen to get hold of Roch's powerful weapon. With the help of his gang, he kidnaps Roch and Hart, takes them to his boat moored close by, and sails to his secret hideout near Bermuda.

That's when we're reminded of Bond villains. Like Blofeld, particularly of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Count d'Artigas has somewhat obscure origins and is not a real count, but assumes the title for respectability. And, anticipating Blofeld in the film of You Only Live Twice, his base is inside a volcano. Actually, the volcano is an artificially created one, formed from a conical mountain that the count engineered to erupt by means of gunpowder and burning seaweed to scare the inhabitants off the small island on which the mountain is situated, but the effect is the same. (If terrifying a population in order to force them off their island sounds familiar, it's because Dr No had the same idea.)

The count resides in a grotto at the base of the mountain, which comprises a series of passages that surround an underground lagoon. Every self-respecting villain needs a shark, and the count is no exception, as an underwater tunnel that joins the sea allows sharks to swim around the lagoon. It must be admitted that the count misses the opportunity to feed anyone to the sharks, but the opportunity's there at least. Sharks, of course, feature frequently in the Bond films, and I'm reminded in particular of Largo's shark pool in Thunderball and Kananga's cave, complete with a pool and shark, that serves as his lair in Live and Let Die.

Blofeld, Stromberg and Drax have their private armies, and so too does Count d'Artigas. In the novel of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, we read that Blofeld's 'staff' at his institute is multi-national and poached from rival criminal organisations. Count d'Artigas has also assembled a multi-national band of villains and criminals who do his bidding. The count is not without a henchman either – a gigantic Malay with herculean strength, who would comfortably fit in the pantheon of Bond henchman, Jaws, May Day, Mr Kil, and Hinx among them.

And like all Bond villains, Count d'Artigas has access to the most advanced technology. He operates a mini submarine that runs on electricity (and can also ram ships that he wishes to attack) and has installed electricity throughout the grotto; no mean feat in the Victorian world. Incidentally, the count stole the submarine at a public demonstration of the vessel in much the same way that Xenia Onatopp stole the Tiger helicopter in GoldenEye.

Jules Verne's novel reminds us that the traits or memes that help define a Bond villain, especially the villains of the films, have older origins. Over the years, the earlier sources, including Facing the Flag and other Verne novels, have largely been forgotten, while the Bond films have become hugely significant in popular culture, to the extent that long-established 'villain memes' are identified more exclusively as 'Bond villain memes'.

Enter the mysterious Count d'Artigas, who's also keen to get hold of Roch's powerful weapon. With the help of his gang, he kidnaps Roch and Hart, takes them to his boat moored close by, and sails to his secret hideout near Bermuda.

That's when we're reminded of Bond villains. Like Blofeld, particularly of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Count d'Artigas has somewhat obscure origins and is not a real count, but assumes the title for respectability. And, anticipating Blofeld in the film of You Only Live Twice, his base is inside a volcano. Actually, the volcano is an artificially created one, formed from a conical mountain that the count engineered to erupt by means of gunpowder and burning seaweed to scare the inhabitants off the small island on which the mountain is situated, but the effect is the same. (If terrifying a population in order to force them off their island sounds familiar, it's because Dr No had the same idea.)

The count resides in a grotto at the base of the mountain, which comprises a series of passages that surround an underground lagoon. Every self-respecting villain needs a shark, and the count is no exception, as an underwater tunnel that joins the sea allows sharks to swim around the lagoon. It must be admitted that the count misses the opportunity to feed anyone to the sharks, but the opportunity's there at least. Sharks, of course, feature frequently in the Bond films, and I'm reminded in particular of Largo's shark pool in Thunderball and Kananga's cave, complete with a pool and shark, that serves as his lair in Live and Let Die.

Blofeld, Stromberg and Drax have their private armies, and so too does Count d'Artigas. In the novel of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, we read that Blofeld's 'staff' at his institute is multi-national and poached from rival criminal organisations. Count d'Artigas has also assembled a multi-national band of villains and criminals who do his bidding. The count is not without a henchman either – a gigantic Malay with herculean strength, who would comfortably fit in the pantheon of Bond henchman, Jaws, May Day, Mr Kil, and Hinx among them.

And like all Bond villains, Count d'Artigas has access to the most advanced technology. He operates a mini submarine that runs on electricity (and can also ram ships that he wishes to attack) and has installed electricity throughout the grotto; no mean feat in the Victorian world. Incidentally, the count stole the submarine at a public demonstration of the vessel in much the same way that Xenia Onatopp stole the Tiger helicopter in GoldenEye.

Jules Verne's novel reminds us that the traits or memes that help define a Bond villain, especially the villains of the films, have older origins. Over the years, the earlier sources, including Facing the Flag and other Verne novels, have largely been forgotten, while the Bond films have become hugely significant in popular culture, to the extent that long-established 'villain memes' are identified more exclusively as 'Bond villain memes'.

Sunday, 15 January 2017

I never left: How the book Bond's biography has remained part of the film Bond's backstory

The James Bond of the cinema may have only passing resemblance to the literary Bond, but there are some biographical details of the literary Bond that the film Bond has retained more or less throughout the film series. However, you won't find many references to them on the screen, but rather in the pages of official James Bond annuals, specials and part-work magazines published over the years.

In James Bond in Focus (1964), one of the earliest special publications to tie in with the release of a Bond film, in this case Goldfinger, a description of Bond's background refers to his flat in the King's Road in Chelsea, Blades club and Bond's elderly Scots housekeeper, all taken from Ian Fleming's novels.

There are no references to Bond's background in the James Bond 007 annuals for 1965 and 1966, but The James Bond Annual of 1968 more than makes up for the oversight, with Bond's biography presented as a confidential Secret Service personnel file. From this we learn that the young Bond attended Eton and Fettes, his parents were Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix, and that he is 6ft 2in tall. We also read in a section of the annual devoted to Bond's cars that Bond's pride and joy was a supercharged Bentley 4½ litre, which Bond's mechanic treated as if it were his own; what's more, the car could reach 100mph with ease, but was destroyed while in pursuit of Sir Hugo Drax.

Various Bond novels were mined for these details. The information on the Bentley was lifted from Moonraker, Bond's height was taken from SMERSH's dossier on Bond in From Russia, with Love (though changed from metric to imperial), while the details of Bond's schooling and parents came from M's obituary of Bond in You Only Live Twice. The inclusion of this last aspect is somewhat ironic, given that the film version of the book, which the annual largely promoted, was the first film to deviate substantially from Fleming's text and included no reference to Bond's background.

For a number of later Bond films, 'specials' took the place of annuals, and some of these allude to Bond's background. The James Bond 007 Moonraker Special (1979) includes a personnel file that lifts the wording of the file in the 1968 annual almost verbatim. There are minor changes – for instance, Bond's height is given in metric (1.83m, the figure from the SMERSH dossier), and his interests change from Greek food to good food – but otherwise the 1968 file had essentially been reprinted. Thus, we also get the details of Bond's childhood: educated at Eton and Fettes, parents Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix.

But there are some additional details. Bond's weight is 76kg, he has a scar down his right cheek and right shoulder and has signs of plastic surgery on the back of his right hand, and Bond is an expert pistol shot, boxer and knife-thrower. All these details, previously ignored, are also taken, word for word, from the SMERSH dossier of From Russia, with Love.

Bond's childhood is the subject of quiz questions in the James Bond For Your Eyes Only Special (1981), with readers invited to name Bond's parents (the answer given, naturally, as Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix), describe how they died (mountain climbing accident), and name the school from which Bond was expelled (Eton). The last two, from the obituary in You Only Live Twice, but not described in earlier annuals or specials, add to the biography associated with the film Bond.

There is no reference to Bond's background in the James Bond Octopussy Special (1983), the A View To A Kill Story Book (1985), or The Official James Bond 007 Fact File (1989), although the last, which coincided with the release of Licence to Kill, does mention Bond's London flat.

In contrast, GoldenEye: The Official Movie Souvenir Magazine (1995) is full of information, which again is lifted from the SMERSH dossier. Thus, Bond is 183cm tall, he weighs 76kg, and has a scar on his right shoulder (the scar on his cheek has evidently disappeared) and signs of plastic surgery on the back of his right hand. In addition, Bond is an expert pistol shot, boxer, and knife-thrower, and, new to the film Bond biography, he does not use disguises, drinks but not to excess, and speaks French and German (so much for Bond's first in oriental languages from Cambridge).

The magazine doesn't mention Bond's parents, but here the film of GoldenEye enlightens us. Alec Trevelyan tells Bond, “We're both orphans, James. But while your parents had the luxury of dying in a climbing accident, mine survived the British betrayal and Stalin's execution squads.”

The details given the GoldenEye film and magazine appeared again in part-work magazine 007 Spy Files (2002). Issue 1 states that Bond is 1.83m tall and weighs 76kg, and has a scar on his right shoulder and another on the back of his right hand. Again, there is no reference to the cheek scar, and the reference to plastic surgery has been dropped. Issue 2 adds that Bond was born in Scotland, he was educated at Eton and Fettes, and that his (unnamed) parents were killed in a climbing accident.

James Bond's dossier, published on a special website (and now available via the MI6: The Home of James Bond 007 website), was significantly updated for the release of Casino Royale (2006), particularly his service history, although Bond's new file retained some familiar details. Bond's parents, Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix died in a climbing accident, Bond attended Eton and Fettes, and he drinks, but not to excess. Further details from the obituary in You Only Live Twice were added to this.

The part-work 007 Spy Cards was published in 2008. Issue 1 gives Bond's height as 1.83m and weight as 76g, and states that he was educated at Eton and Fettes. It drops Bond's fluency in French and German, but restores his first in oriental languages from Cambridge. Bond's file adds that his parents were killed in a climbing accident, and the sharp-eyed reader might spot his parents' names on an image of his birth certificate. Bond's skills are now hand-to-hand combat, running, skiing, swimming and climbing, rather than shooting, boxing and knife-throwing.

Very little of this information, re-emerging intermittently over the years, has made it to the screen, but the Daniel Craig era has seen a return to Fleming's Bond to the extent that Bond's biography has provided essential plot points. In Skyfall (2012), M and Bond allude to the death of Bond's parents, and in the graveyard of the chapel close to Skyfall, there is a gravestone recording the death of Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix Bond. And in Spectre (2015), more is made of Bond's childhood since the death of his parents. There is still no mention of Bond's height or weight, though.

Far from ignoring the Bond novels, the various official publications that have tied in with film releases, if not the films themselves, have demonstrated that Ian Fleming's description of Bond's background and characteristics has remained part of the film Bond's dossier.

There has been variation, and over time details have been dropped (and sometimes restored). Some details, though, have survived unchanged, and have been repeated often over a period of almost 50 years. These include Bond's height, weight, childhood education, and the details of Bond's parents. Ultimately, this is testament to Fleming's writing, in this case the SMERSH dossier of From Russia, with Love, and M's obituary in You Only Live Twice, which has proved to be enduring and highly adaptable.

In James Bond in Focus (1964), one of the earliest special publications to tie in with the release of a Bond film, in this case Goldfinger, a description of Bond's background refers to his flat in the King's Road in Chelsea, Blades club and Bond's elderly Scots housekeeper, all taken from Ian Fleming's novels.

There are no references to Bond's background in the James Bond 007 annuals for 1965 and 1966, but The James Bond Annual of 1968 more than makes up for the oversight, with Bond's biography presented as a confidential Secret Service personnel file. From this we learn that the young Bond attended Eton and Fettes, his parents were Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix, and that he is 6ft 2in tall. We also read in a section of the annual devoted to Bond's cars that Bond's pride and joy was a supercharged Bentley 4½ litre, which Bond's mechanic treated as if it were his own; what's more, the car could reach 100mph with ease, but was destroyed while in pursuit of Sir Hugo Drax.

Various Bond novels were mined for these details. The information on the Bentley was lifted from Moonraker, Bond's height was taken from SMERSH's dossier on Bond in From Russia, with Love (though changed from metric to imperial), while the details of Bond's schooling and parents came from M's obituary of Bond in You Only Live Twice. The inclusion of this last aspect is somewhat ironic, given that the film version of the book, which the annual largely promoted, was the first film to deviate substantially from Fleming's text and included no reference to Bond's background.

For a number of later Bond films, 'specials' took the place of annuals, and some of these allude to Bond's background. The James Bond 007 Moonraker Special (1979) includes a personnel file that lifts the wording of the file in the 1968 annual almost verbatim. There are minor changes – for instance, Bond's height is given in metric (1.83m, the figure from the SMERSH dossier), and his interests change from Greek food to good food – but otherwise the 1968 file had essentially been reprinted. Thus, we also get the details of Bond's childhood: educated at Eton and Fettes, parents Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix.

But there are some additional details. Bond's weight is 76kg, he has a scar down his right cheek and right shoulder and has signs of plastic surgery on the back of his right hand, and Bond is an expert pistol shot, boxer and knife-thrower. All these details, previously ignored, are also taken, word for word, from the SMERSH dossier of From Russia, with Love.

Bond's childhood is the subject of quiz questions in the James Bond For Your Eyes Only Special (1981), with readers invited to name Bond's parents (the answer given, naturally, as Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix), describe how they died (mountain climbing accident), and name the school from which Bond was expelled (Eton). The last two, from the obituary in You Only Live Twice, but not described in earlier annuals or specials, add to the biography associated with the film Bond.

There is no reference to Bond's background in the James Bond Octopussy Special (1983), the A View To A Kill Story Book (1985), or The Official James Bond 007 Fact File (1989), although the last, which coincided with the release of Licence to Kill, does mention Bond's London flat.

In contrast, GoldenEye: The Official Movie Souvenir Magazine (1995) is full of information, which again is lifted from the SMERSH dossier. Thus, Bond is 183cm tall, he weighs 76kg, and has a scar on his right shoulder (the scar on his cheek has evidently disappeared) and signs of plastic surgery on the back of his right hand. In addition, Bond is an expert pistol shot, boxer, and knife-thrower, and, new to the film Bond biography, he does not use disguises, drinks but not to excess, and speaks French and German (so much for Bond's first in oriental languages from Cambridge).

The magazine doesn't mention Bond's parents, but here the film of GoldenEye enlightens us. Alec Trevelyan tells Bond, “We're both orphans, James. But while your parents had the luxury of dying in a climbing accident, mine survived the British betrayal and Stalin's execution squads.”

The details given the GoldenEye film and magazine appeared again in part-work magazine 007 Spy Files (2002). Issue 1 states that Bond is 1.83m tall and weighs 76kg, and has a scar on his right shoulder and another on the back of his right hand. Again, there is no reference to the cheek scar, and the reference to plastic surgery has been dropped. Issue 2 adds that Bond was born in Scotland, he was educated at Eton and Fettes, and that his (unnamed) parents were killed in a climbing accident.

James Bond's dossier, published on a special website (and now available via the MI6: The Home of James Bond 007 website), was significantly updated for the release of Casino Royale (2006), particularly his service history, although Bond's new file retained some familiar details. Bond's parents, Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix died in a climbing accident, Bond attended Eton and Fettes, and he drinks, but not to excess. Further details from the obituary in You Only Live Twice were added to this.

The part-work 007 Spy Cards was published in 2008. Issue 1 gives Bond's height as 1.83m and weight as 76g, and states that he was educated at Eton and Fettes. It drops Bond's fluency in French and German, but restores his first in oriental languages from Cambridge. Bond's file adds that his parents were killed in a climbing accident, and the sharp-eyed reader might spot his parents' names on an image of his birth certificate. Bond's skills are now hand-to-hand combat, running, skiing, swimming and climbing, rather than shooting, boxing and knife-throwing.

Very little of this information, re-emerging intermittently over the years, has made it to the screen, but the Daniel Craig era has seen a return to Fleming's Bond to the extent that Bond's biography has provided essential plot points. In Skyfall (2012), M and Bond allude to the death of Bond's parents, and in the graveyard of the chapel close to Skyfall, there is a gravestone recording the death of Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix Bond. And in Spectre (2015), more is made of Bond's childhood since the death of his parents. There is still no mention of Bond's height or weight, though.

Far from ignoring the Bond novels, the various official publications that have tied in with film releases, if not the films themselves, have demonstrated that Ian Fleming's description of Bond's background and characteristics has remained part of the film Bond's dossier.

There has been variation, and over time details have been dropped (and sometimes restored). Some details, though, have survived unchanged, and have been repeated often over a period of almost 50 years. These include Bond's height, weight, childhood education, and the details of Bond's parents. Ultimately, this is testament to Fleming's writing, in this case the SMERSH dossier of From Russia, with Love, and M's obituary in You Only Live Twice, which has proved to be enduring and highly adaptable.

Thursday, 5 January 2017

When James Bond dreamt of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe seems an unlikely influence on Ian Fleming's writing, but the 19th-century poet, story-teller, and master of the macabre nevertheless made his mark in the James Bond novels.

Ian Fleming mentions Poe three times in the Bond novels. There is one reference in Moonraker (1955); Fleming compares the ominous ticking inside the Moonraker rocket before launch to “the beating heart in Poe's story” (probably 'The Tell-Tale Heart' (1843), in which “the beating of the old man's heart...increased my fury, as the beating of the drum stimulates the soldier into courage”).

Fleming himself had a fondness for the macabre, and it is appropriate that his most macabre novel, You Only Live Twice (1965), contains two references to Poe. When Tiger Tanaka describes Dr Shatterhand's castle of death, Bond is reminded of Poe, Le Fanu, Bram Stoker and Ambrose Bierce. Later, when Bond encounters Shatterhand, now revealed to be Blofeld, he comments on Blofeld's genius for creating a shrine to death. “People read about such fantasies in the works of Poe, Lautréamont, de Sade.”

But there is another allusion to Poe. In his 1842 story, 'The Mystery of Marie Rogêt', in which the detective C Auguste Dupin investigates the unsolved murder of Marie Rogêt, the unnamed narrator is subjected to a series of tests on the matter of dreams. At one point he states that “when one dreams, and, in the dream, suspects that he dreams, the suspicion never fails to confirm itself, and the sleeper is almost instantly aroused. Thus Novalis errs not in saying that 'we are near waking when we dream that we dream.'”

If this passage seems familiar, then it is because Fleming had the same idea in Casino Royale (1953). Chapter 19, which describes Bond's recovery after his savage beating at the hands of Le Chiffre, begins, “You are about to awake when you dream that you are dreaming.”

The idea is an attractive one, and interestingly Fleming isn't the first novelist to allude to it. For instance, in Jules Verne's 1897 novel, Le Sphinx des Glaces, which imagines that Poe's 1838 novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, is a true account of a voyage to Antarctica, the protagonist Mr Jeorling describes how he “dreamed that I was dreaming,” continuing that “when one suspects that one is dreaming, the waking comes almost instantly.”

The references to Edgar Allan Poe in the Bond novels confirm that Ian Fleming was familiar with the writer's work. Possibly the young Ian listened to Poe's stories, along with those of Buchan and Rohmer, at Durnford School. But wherever and whenever Fleming read the stories, they stayed with him, and it is inevitable that the ideas within them would re-emerge in Fleming's own work.

Ian Fleming mentions Poe three times in the Bond novels. There is one reference in Moonraker (1955); Fleming compares the ominous ticking inside the Moonraker rocket before launch to “the beating heart in Poe's story” (probably 'The Tell-Tale Heart' (1843), in which “the beating of the old man's heart...increased my fury, as the beating of the drum stimulates the soldier into courage”).

|

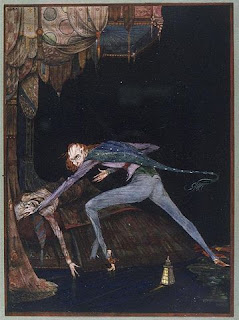

| An illustration from 'Tell-Tale Heart' |

But there is another allusion to Poe. In his 1842 story, 'The Mystery of Marie Rogêt', in which the detective C Auguste Dupin investigates the unsolved murder of Marie Rogêt, the unnamed narrator is subjected to a series of tests on the matter of dreams. At one point he states that “when one dreams, and, in the dream, suspects that he dreams, the suspicion never fails to confirm itself, and the sleeper is almost instantly aroused. Thus Novalis errs not in saying that 'we are near waking when we dream that we dream.'”

|

| An illustration from The Mystery of Marie Roget |

The idea is an attractive one, and interestingly Fleming isn't the first novelist to allude to it. For instance, in Jules Verne's 1897 novel, Le Sphinx des Glaces, which imagines that Poe's 1838 novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, is a true account of a voyage to Antarctica, the protagonist Mr Jeorling describes how he “dreamed that I was dreaming,” continuing that “when one suspects that one is dreaming, the waking comes almost instantly.”

The references to Edgar Allan Poe in the Bond novels confirm that Ian Fleming was familiar with the writer's work. Possibly the young Ian listened to Poe's stories, along with those of Buchan and Rohmer, at Durnford School. But wherever and whenever Fleming read the stories, they stayed with him, and it is inevitable that the ideas within them would re-emerge in Fleming's own work.

Sunday, 1 January 2017

Some classic James Bond helicopter scenes in Lego

There were some very thoughtful and exciting gifts waiting for me under the tree this Christmas, including Lego figures of James Bond and Skyfall's Raoul Silva, and a Lego helicopter to go with them. The presents got me thinking about some of the many scenes in the Bond films that featured helicopters, and, following my earlier attempts to build Bond vehicles, how I could recreate them in Lego.

The helicopter set that I had been given was a gunship from the Ultra Agents range. It wasn't too dissimilar from the Tiger helicopter from GoldenEye, so I turned to that film first. The helicopter is a two-seater, so I simply put Bond in the front seat of the cockpit and a female figure in the back seat to represent Natalya Simonova and recreate the scene where both have been captured and bound to the cockpit seats. Here Natalya has just woken Bond up.

The pre-titles sequence of For Your Eyes Only is up there with the best of the opening sequences. Bond is picked up in a Universal Exports helicopter, which is then remotely hijacked by a Blofeld-like figure (now officially acknowledged to be Blofeld). With the pilot out of action, Bond clambers outside the aircraft, opens the pilot's door, climbs back inside, takes control and deals with Blofeld (declining the offer of a delicatessen in stainless steel). My Lego collection isn't that extensive, but I managed to find enough pieces to build something that resembled the helicopter. I had Bond dangle outside and used an image of Beckton Gas Works, where the scene was filmed, as background.

I was keen to recreate the scene in From Russia With Love where Bond is being pursued by a helicopter in the Scottish highlands standing in for Turkey, but the design of the helicopter was too much of a challenge for my limited resources. Instead, I looked to On Her Majesty's Secret Service (appropriately enough, being a Christmas film) and the helicopter attack on Piz Gloria.

As I was watching the sequence again, looking for a good action moment involving Bond and a helicopter, I realised that Bond isn't particularly visible during the arrival of the helicopters at Piz Gloria. The sequence focuses on the approach of the helicopters, long-distance shots of Draco's men jumping out, and Tracy's fight with Blofeld's goons, but Bond isn't seen in close-up until he's out of the helicopter and sliding towards the main building. That hasn't stopped me, however, from showing Bond more clearly jumping out of the helicopter – in Lego, at least.

The helicopter itself was fairly easily rendered in Lego, and I was especially lucky to have a brick with a Red Cross sticker. I found an image of Piz Gloria to use as the background. Bond is wearing Silva's white jacket, which I thought it went better with the snow-covered slopes.

I don't pretend that my models are particularly accurate, but I've certainly had fun making them. There are plenty more helicopter moments in the Bond films, so watch this space for more of them recreated in Lego!

|

| James Bond and Raoul Silva as Lego figures |

|

| Inside the Tiger helicopter in GoldenEye |

|

| Spot the difference. The opening sequence of For Your Eyes Only |

As I was watching the sequence again, looking for a good action moment involving Bond and a helicopter, I realised that Bond isn't particularly visible during the arrival of the helicopters at Piz Gloria. The sequence focuses on the approach of the helicopters, long-distance shots of Draco's men jumping out, and Tracy's fight with Blofeld's goons, but Bond isn't seen in close-up until he's out of the helicopter and sliding towards the main building. That hasn't stopped me, however, from showing Bond more clearly jumping out of the helicopter – in Lego, at least.

|

| The helicopter assault on Piz Gloria |

I don't pretend that my models are particularly accurate, but I've certainly had fun making them. There are plenty more helicopter moments in the Bond films, so watch this space for more of them recreated in Lego!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)